Contents

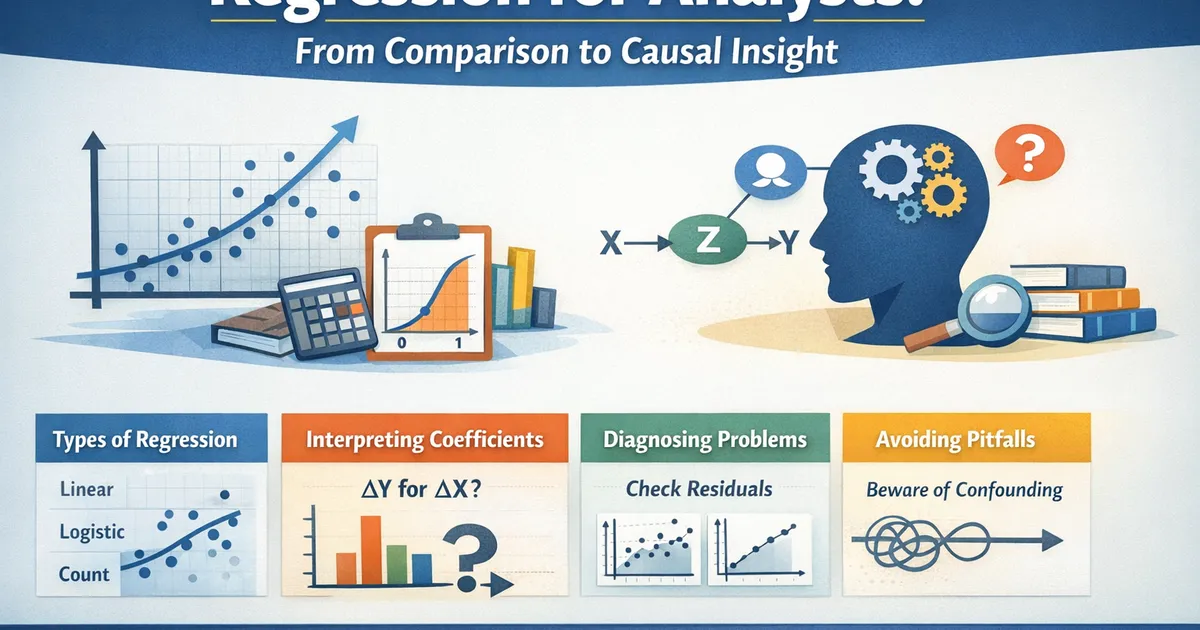

Regression for Analysts: From Comparison to Causal Insight

A comprehensive guide to regression analysis for product and data analysts. Learn when to use linear, logistic, and count regression, how to diagnose problems, interpret coefficients correctly, and avoid common pitfalls that lead to misleading conclusions.

Quick Hits

- •Regression = flexible framework for understanding relationships between variables

- •Linear for continuous outcomes, logistic for binary, Poisson/NB for counts

- •Coefficients answer: 'What's the expected change in Y for a unit change in X, holding others constant?'

- •'Holding others constant' is a statistical adjustment, not an experimental control

- •Diagnostics matter more than the regression itself - always check residuals

TL;DR

Regression is a framework for modeling how one or more predictor variables relate to an outcome. Linear regression handles continuous outcomes, logistic regression handles binary outcomes (yes/no), and Poisson/negative binomial regression handles counts. This guide covers when to use each type, how to interpret coefficients correctly, essential diagnostics, and common mistakes that lead analysts astray. The key insight: regression adjusts for included covariates, but "adjusting for X" is not the same as "experimentally controlling X."

Why Regression Matters for Analysts

Regression answers questions that simple comparisons can't:

-

What's the relationship between X and Y after accounting for Z?

- Does the marketing campaign increase revenue after controlling for seasonality?

-

How much does Y change when X changes by one unit?

- For each additional day of onboarding, how much does retention increase?

-

Which predictors matter most?

- Among pricing, features, and support, which drives upgrade decisions?

-

What would Y be for a new observation with specific X values?

- What's the expected lifetime value for a user with these characteristics?

The Regression Family

Linear Regression: Continuous Outcomes

Use when your outcome is a continuous number (revenue, time, satisfaction score).

Interpretation: = expected change in Y for a one-unit increase in , holding other predictors constant.

Example: Revenue = 100 + 5(emails sent) + 20(has premium) + error

- Each additional email is associated with $5 more revenue

- Premium users have $20 higher revenue on average

Logistic Regression: Binary Outcomes

Use when your outcome is yes/no, converted/not, churned/retained.

Interpretation: = odds ratio for a one-unit increase in .

Example: Conversion = f(price, has free trial, referral source)

- : each $1 price increase reduces conversion odds by 15%

Poisson/Negative Binomial: Count Outcomes

Use when your outcome is a count (purchases, logins, support tickets).

Interpretation: = multiplicative change in expected count.

Example: Support tickets = f(days since signup, plan type)

- : each additional day reduces expected tickets by 2%

Coefficient Interpretation: Getting It Right

The Fundamental Statement

For a coefficient :

" is the expected change in Y for a one-unit increase in , holding all other predictors in the model constant."

What "Holding Constant" Actually Means

This is statistical adjustment, not experimental control:

Statistical adjustment: "Among people with the same values of other predictors, how does Y vary with ?"

Experimental control: "If we randomly assigned values while keeping everything else fixed, what would happen?"

These are only equivalent under strong assumptions (no unmeasured confounders, correct model specification).

Example: Education and Salary

Model: Salary = + (Years of Education) + (Experience)

= $5,000

Correct interpretation: "Among people with the same experience level, each additional year of education is associated with $5,000 higher salary."

Incorrect interpretation: "If you get one more year of education, your salary will increase by $5,000."

The second interpretation assumes no confounding—maybe more educated people have other characteristics (motivation, networks, family resources) that also affect salary.

Building a Regression Model

Step 1: Define the Question

What relationship are you trying to understand or predict?

- Descriptive: What factors are associated with higher retention?

- Predictive: What's the expected revenue for this user?

- Causal (with caution): Does the new feature increase engagement?

Step 2: Choose the Right Model Type

| Outcome Type | Model | R Function | Python Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Continuous | Linear | lm() |

statsmodels.OLS |

| Binary (0/1) | Logistic | glm(..., family=binomial) |

statsmodels.Logit |

| Count | Poisson | glm(..., family=poisson) |

statsmodels.Poisson |

| Overdispersed count | Negative Binomial | MASS::glm.nb() |

statsmodels.NegativeBinomial |

| Bounded (0-1) | Beta | betareg::betareg() |

statsmodels.GLM with beta family |

Step 3: Select Predictors

Include:

- Variables directly relevant to your research question

- Known confounders (affect both predictor of interest and outcome)

- Variables that improve prediction (if prediction is the goal)

Exclude:

- Variables on the causal path between X and Y (mediators)

- Variables that could induce collider bias

- Highly collinear variables (pick one or combine)

Step 4: Fit and Diagnose

Fit the model, then check:

- Residual plots for assumption violations

- Influential observations

- Multicollinearity (VIF)

- Model fit metrics (R², deviance, AIC/BIC)

Step 5: Interpret Carefully

- Report effect sizes with confidence intervals

- Distinguish association from causation

- Acknowledge limitations and alternative explanations

Diagnostics: The Most Important Part

For Linear Regression

Residuals vs. Fitted Plot (Linearity, Homoscedasticity)

- Should show random scatter around zero

- Patterns indicate non-linearity or heteroscedasticity

Q-Q Plot (Normality)

- Points should follow the diagonal line

- Deviations at tails suggest non-normality

Scale-Location Plot (Homoscedasticity)

- Should show horizontal band with even spread

- Funnel shape indicates heteroscedasticity

Residuals vs. Leverage Plot (Influential Points)

- Watch for points with high Cook's distance (>1 or >4/n)

For Logistic Regression

ROC Curve and AUC

- Measures discrimination ability

- AUC > 0.7 is acceptable, > 0.8 is good, > 0.9 is excellent

Calibration Plot

- Predicted probabilities should match observed rates

- Group predictions into bins and compare to actual outcome rates

Hosmer-Lemeshow Test

- Tests whether predicted probabilities match observed outcomes

- Non-significant p-value suggests good fit (but sensitive to sample size)

For Count Models

Dispersion Check

- Poisson assumes mean = variance

- If variance >> mean, use negative binomial

- Check: ratio of Pearson chi-square to degrees of freedom

Zero-Inflation Check

- More zeros than Poisson/NB predicts?

- Consider zero-inflated models

Code: Complete Regression Workflow

Python

import numpy as np

import pandas as pd

import statsmodels.api as sm

import statsmodels.formula.api as smf

from statsmodels.stats.outliers_influence import variance_inflation_factor

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import seaborn as sns

def run_linear_regression(data, formula):

"""

Complete linear regression workflow with diagnostics.

Parameters:

-----------

data : pd.DataFrame

Dataset

formula : str

Patsy formula (e.g., 'y ~ x1 + x2')

Returns:

--------

dict with model, summary, and diagnostic flags

"""

# Fit model

model = smf.ols(formula, data=data).fit()

# Extract components for diagnostics

fitted = model.fittedvalues

residuals = model.resid

standardized_resid = model.get_influence().resid_studentized_internal

leverage = model.get_influence().hat_matrix_diag

cooks_d = model.get_influence().cooks_distance[0]

# Calculate VIF for multicollinearity

X = model.model.exog

vif_data = pd.DataFrame({

'Variable': model.model.exog_names,

'VIF': [variance_inflation_factor(X, i) for i in range(X.shape[1])]

})

# Diagnostic flags

flags = []

# High Cook's distance

high_cooks = np.sum(cooks_d > 4/len(data))

if high_cooks > 0:

flags.append(f"{high_cooks} observations with Cook's d > 4/n")

# High VIF

high_vif = vif_data[vif_data['VIF'] > 5]['Variable'].tolist()

if 'Intercept' in high_vif:

high_vif.remove('Intercept')

if high_vif:

flags.append(f"High VIF (>5): {high_vif}")

# Heteroscedasticity (Breusch-Pagan)

from statsmodels.stats.diagnostic import het_breuschpagan

bp_stat, bp_p, _, _ = het_breuschpagan(residuals, model.model.exog)

if bp_p < 0.05:

flags.append(f"Heteroscedasticity detected (BP p={bp_p:.4f})")

return {

'model': model,

'summary': model.summary(),

'vif': vif_data,

'diagnostics': {

'fitted': fitted,

'residuals': residuals,

'standardized_resid': standardized_resid,

'leverage': leverage,

'cooks_d': cooks_d

},

'flags': flags,

'r_squared': model.rsquared,

'adj_r_squared': model.rsquared_adj

}

def plot_linear_diagnostics(result, figsize=(12, 10)):

"""Create diagnostic plots for linear regression."""

diag = result['diagnostics']

fig, axes = plt.subplots(2, 2, figsize=figsize)

# 1. Residuals vs Fitted

ax1 = axes[0, 0]

ax1.scatter(diag['fitted'], diag['residuals'], alpha=0.6)

ax1.axhline(y=0, color='red', linestyle='--')

ax1.set_xlabel('Fitted Values')

ax1.set_ylabel('Residuals')

ax1.set_title('Residuals vs Fitted')

# Add lowess smoothing

from statsmodels.nonparametric.smoothers_lowess import lowess

smooth = lowess(diag['residuals'], diag['fitted'], frac=0.3)

ax1.plot(smooth[:, 0], smooth[:, 1], color='red', linewidth=2)

# 2. Q-Q Plot

ax2 = axes[0, 1]

from scipy import stats

stats.probplot(diag['standardized_resid'], dist="norm", plot=ax2)

ax2.set_title('Normal Q-Q')

# 3. Scale-Location

ax3 = axes[1, 0]

sqrt_abs_resid = np.sqrt(np.abs(diag['standardized_resid']))

ax3.scatter(diag['fitted'], sqrt_abs_resid, alpha=0.6)

ax3.set_xlabel('Fitted Values')

ax3.set_ylabel('√|Standardized Residuals|')

ax3.set_title('Scale-Location')

smooth = lowess(sqrt_abs_resid, diag['fitted'], frac=0.3)

ax3.plot(smooth[:, 0], smooth[:, 1], color='red', linewidth=2)

# 4. Residuals vs Leverage

ax4 = axes[1, 1]

ax4.scatter(diag['leverage'], diag['standardized_resid'], alpha=0.6)

ax4.axhline(y=0, color='grey', linestyle='--')

ax4.set_xlabel('Leverage')

ax4.set_ylabel('Standardized Residuals')

ax4.set_title('Residuals vs Leverage')

# Add Cook's distance contours

xlim = ax4.get_xlim()

ylim = ax4.get_ylim()

for thresh in [0.5, 1.0]:

x = np.linspace(0.001, xlim[1], 50)

y = np.sqrt(thresh * len(diag['fitted']) * (1-x) / x)

ax4.plot(x, y, 'r--', linewidth=0.5)

ax4.plot(x, -y, 'r--', linewidth=0.5)

plt.tight_layout()

return fig

def run_logistic_regression(data, formula):

"""

Logistic regression workflow with diagnostics.

"""

# Fit model

model = smf.logit(formula, data=data).fit(disp=0)

# Calculate predicted probabilities

pred_probs = model.predict()

# Calculate odds ratios with CIs

params = model.params

conf = model.conf_int()

odds_ratios = pd.DataFrame({

'Variable': params.index,

'Coefficient': params.values,

'Odds Ratio': np.exp(params.values),

'OR CI Lower': np.exp(conf[0].values),

'OR CI Upper': np.exp(conf[1].values),

'P-value': model.pvalues.values

})

return {

'model': model,

'summary': model.summary(),

'odds_ratios': odds_ratios,

'pred_probs': pred_probs,

'aic': model.aic,

'bic': model.bic

}

# Example usage

if __name__ == "__main__":

# Generate sample data

np.random.seed(42)

n = 500

data = pd.DataFrame({

'x1': np.random.normal(0, 1, n),

'x2': np.random.normal(0, 1, n),

'x3': np.random.choice(['A', 'B', 'C'], n)

})

data['y'] = 5 + 2*data['x1'] - 1*data['x2'] + \

np.where(data['x3']=='B', 3, np.where(data['x3']=='C', -2, 0)) + \

np.random.normal(0, 2, n)

# Run regression

result = run_linear_regression(data, 'y ~ x1 + x2 + C(x3)')

print("Regression Summary")

print("=" * 60)

print(result['summary'])

print("\nVIF Table:")

print(result['vif'])

print("\nDiagnostic Flags:")

for flag in result['flags']:

print(f" - {flag}")

R

library(tidyverse)

library(broom)

library(car) # For VIF

library(performance) # For comprehensive diagnostics

run_linear_regression <- function(formula, data) {

#' Complete linear regression workflow

model <- lm(formula, data = data)

# Calculate VIF

vif_values <- tryCatch(

vif(model),

error = function(e) NA

)

# Diagnostic tests

# Breusch-Pagan for heteroscedasticity

bp_test <- lmtest::bptest(model)

# Shapiro-Wilk for normality (on sample of residuals if n > 5000)

resids <- residuals(model)

if (length(resids) > 5000) {

resids <- sample(resids, 5000)

}

normality_test <- shapiro.test(resids)

# Influential observations

cooks_d <- cooks.distance(model)

influential <- sum(cooks_d > 4/nrow(data))

# Compile flags

flags <- c()

if (bp_test$p.value < 0.05) {

flags <- c(flags, sprintf("Heteroscedasticity detected (BP p=%.4f)", bp_test$p.value))

}

if (normality_test$p.value < 0.05) {

flags <- c(flags, sprintf("Non-normality detected (SW p=%.4f)", normality_test$p.value))

}

if (any(vif_values > 5, na.rm = TRUE)) {

high_vif <- names(vif_values)[vif_values > 5]

flags <- c(flags, sprintf("High VIF (>5): %s", paste(high_vif, collapse=", ")))

}

if (influential > 0) {

flags <- c(flags, sprintf("%d observations with Cook's d > 4/n", influential))

}

list(

model = model,

summary = summary(model),

tidy = tidy(model, conf.int = TRUE),

glance = glance(model),

vif = vif_values,

flags = flags

)

}

plot_diagnostics <- function(model) {

#' Create diagnostic plots using base R

par(mfrow = c(2, 2))

plot(model)

par(mfrow = c(1, 1))

}

run_logistic_regression <- function(formula, data) {

#' Logistic regression with odds ratios

model <- glm(formula, data = data, family = binomial)

# Odds ratios with CIs

or_table <- exp(cbind(

OR = coef(model),

confint(model)

))

# Model fit

null_dev <- model$null.deviance

resid_dev <- model$deviance

pseudo_r2 <- 1 - (resid_dev / null_dev)

list(

model = model,

summary = summary(model),

odds_ratios = or_table,

tidy = tidy(model, conf.int = TRUE, exponentiate = TRUE),

aic = AIC(model),

pseudo_r2 = pseudo_r2

)

}

run_poisson_regression <- function(formula, data) {

#' Poisson regression with overdispersion check

model <- glm(formula, data = data, family = poisson)

# Overdispersion check

pearson_resid <- sum(residuals(model, type = "pearson")^2)

df_resid <- model$df.residual

dispersion <- pearson_resid / df_resid

# Rate ratios with CIs

rr_table <- exp(cbind(

RR = coef(model),

confint(model)

))

flags <- c()

if (dispersion > 1.5) {

flags <- c(flags, sprintf("Overdispersion detected (%.2f > 1.5). Consider negative binomial.", dispersion))

}

list(

model = model,

summary = summary(model),

rate_ratios = rr_table,

dispersion = dispersion,

flags = flags

)

}

# Example usage

set.seed(42)

n <- 500

data <- tibble(

x1 = rnorm(n),

x2 = rnorm(n),

x3 = sample(c("A", "B", "C"), n, replace = TRUE)

) %>%

mutate(

y = 5 + 2*x1 - 1*x2 +

case_when(x3 == "B" ~ 3, x3 == "C" ~ -2, TRUE ~ 0) +

rnorm(n, sd = 2)

)

# Run regression

result <- run_linear_regression(y ~ x1 + x2 + x3, data)

cat("Regression Results\n")

cat(strrep("=", 60), "\n")

print(result$tidy)

cat("\nModel Fit:\n")

print(result$glance)

cat("\nDiagnostic Flags:\n")

for (flag in result$flags) {

cat(" -", flag, "\n")

}

Common Mistakes and How to Avoid Them

Mistake 1: Interpreting Coefficients as Causal Effects

Wrong: "Our model shows that each additional year of education increases salary by $5,000."

Right: "Our model shows that education is associated with $5,000 higher salary per year, after adjusting for experience. This may reflect causal effects, selection effects, or unmeasured confounders."

Fix: Be precise about what regression can and cannot tell you. Use causal language only for experimental data.

Mistake 2: Including Post-Treatment Variables

If X → M → Y, controlling for M blocks the causal path from X to Y.

Wrong: Testing if a marketing campaign (X) affects purchases (Y) while controlling for website visits (M) that the campaign causes.

Right: Don't control for mediators. Report total effect (without M) and potentially decompose direct/indirect effects if that's your question.

Mistake 3: Ignoring Diagnostics

Wrong: Running regression, seeing , declaring success.

Right: Check residual plots before interpreting any coefficients. Violations can make standard errors wrong and coefficients biased.

Mistake 4: Stepwise Selection

Wrong: Using automated stepwise procedures to select variables.

Right: Select variables based on theory and research questions. Use cross-validation for purely predictive models.

Mistake 5: Overfitting

Wrong: Adding many predictors to maximize R².

Right: Report adjusted R². Use AIC/BIC for model comparison. Consider holdout validation for predictive models.

Mistake 6: Ignoring Multicollinearity

Wrong: Including highly correlated predictors and interpreting their coefficients.

Right: Check VIF. If VIF > 5-10, consider combining variables or dropping redundant ones.

Regression vs. Simple Tests: A Unified View

Regression subsumes many common tests:

| Simple Test | Regression Equivalent |

|---|---|

| One-sample t-test | Regression with intercept only, test |

| Two-sample t-test | y ~ group (dummy coded) |

| Paired t-test | y_diff ~ 1 (regression on differences) |

| One-way ANOVA | y ~ factor (dummy coded) |

| Two-way ANOVA | y ~ factor1 * factor2 |

| Correlation test | y ~ x (standardized both) |

| Chi-square test | Logistic regression on counts |

Why this matters: Understanding regression as a general framework helps you see when simple tests are appropriate and when you need more flexibility.

When Regression Isn't Enough

For Causal Inference

Regression alone can't handle unmeasured confounding. Consider:

- Randomized experiments: Gold standard for causal claims

- Instrumental variables: When you have a valid instrument

- Regression discontinuity: When treatment is assigned by a threshold

- Difference-in-differences: When you have pre/post and treatment/control

For Non-Linear Relationships

Standard regression assumes linear relationships (in parameters). For complex patterns:

- Polynomial terms: y ~ x + x² for U-shaped relationships

- Splines: Flexible local fitting

- GAMs: Generalized additive models for smooth non-linearities

- Machine learning: Random forests, gradient boosting for prediction

For Hierarchical/Clustered Data

When observations aren't independent (students in classrooms, users across sessions):

- Mixed effects models: Account for group structure

- Cluster-robust standard errors: At minimum, adjust SEs

- GEE: Generalized estimating equations

The Analyst's Regression Checklist

Before Fitting

- Research question is clear

- Outcome variable type identified (continuous, binary, count)

- Predictors selected based on theory/question (not p-values)

- Sample size adequate for planned predictors

- Data cleaned (missing values handled, outliers examined)

After Fitting

- Residuals vs. fitted shows no patterns

- Q-Q plot shows approximate normality (linear regression)

- Scale-location plot shows homoscedasticity

- No highly influential observations (or understood)

- VIF < 5 for all predictors (or multicollinearity acknowledged)

- Model makes substantive sense

When Reporting

- Effect sizes with confidence intervals

- Clear distinction between association and causation

- Limitations acknowledged

- Sensitivity to model choices discussed

Related Articles in This Cluster

Regression Fundamentals

- Linear Regression Assumptions and Diagnostics - Deep dive on diagnostics

- Regression vs. t-test/ANOVA: A Unifying View - When simpler tests suffice

Specialized Models

- Logistic Regression: Interpretation and Pitfalls - Binary outcomes

- Poisson vs. Negative Binomial - Count outcomes

Handling Complications

- Interaction Terms - Treatment × segment effects

- Robust Standard Errors - Heteroscedasticity fixes

- Collinearity - When predictors correlate

- Feature Scaling and Transforms - Preprocessing decisions

Key Takeaway

Regression is the analyst's most versatile tool—it unifies simple comparisons (t-tests, ANOVA) and correlation into one framework that handles continuous predictors, multiple covariates, and different outcome types. But versatility requires vigilance: always check diagnostics, interpret "controlling for" correctly (it's statistical adjustment, not experimental control), and remember that without randomization, coefficients show association, not causation. Master regression, and you'll have a framework for understanding relationships in almost any data.

References

- https://www.stat.berkeley.edu/~aldous/157/Papers/Fox.pdf

- https://www.amazon.com/Regression-Stories-Prediction-Quantitative-Analysis/dp/1107676517

- https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/2515245917745629

- Fox, J. (2015). Applied regression analysis and generalized linear models. Sage Publications.

- Gelman, A., Hill, J., & Vehtari, A. (2020). Regression and other stories. Cambridge University Press.

- Westfall, J., & Yarkoni, T. (2016). Statistically controlling for confounding constructs is harder than you think. *PLoS ONE*, 11(3), e0152719.

Frequently Asked Questions

When should I use regression instead of a t-test or ANOVA?

What's the difference between linear and logistic regression?

Can regression prove causation?

How do I know if my regression is valid?

Key Takeaway

Regression is the analyst's Swiss Army knife - it unifies t-tests, ANOVA, and correlation into one flexible framework. But flexibility creates responsibility: you must check assumptions, interpret coefficients correctly (association, not causation without experiments), and understand what 'controlling for' actually means.