Contents

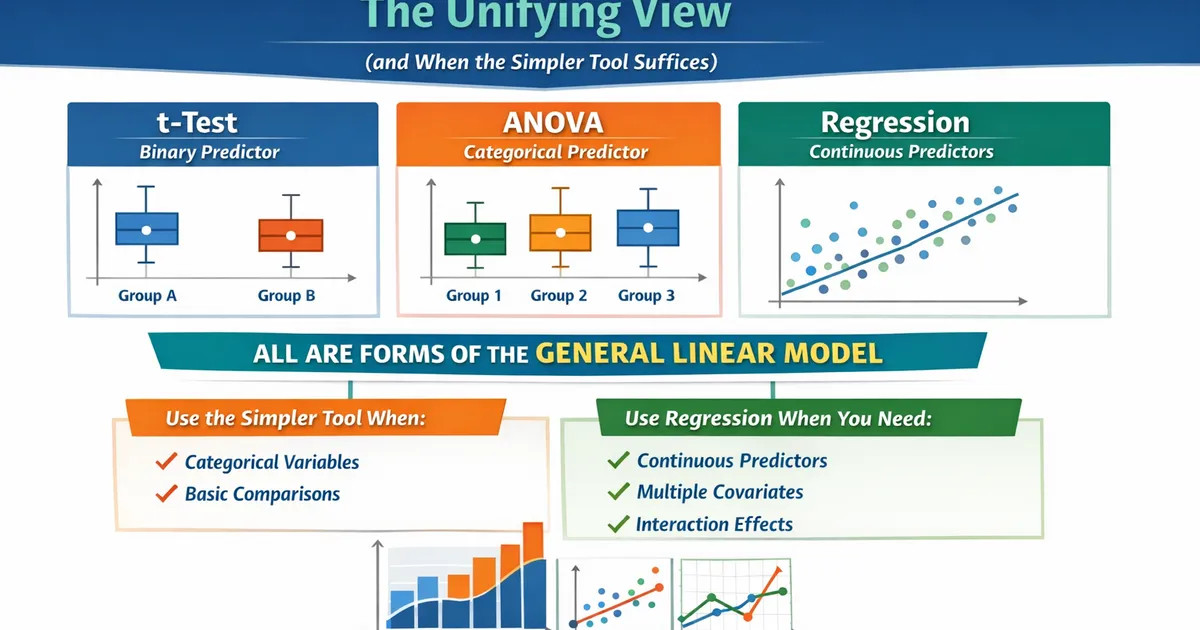

Regression vs. t-Test vs. ANOVA: The Unifying View (and When the Simpler Tool Suffices)

Understand how t-tests, ANOVA, and regression are all the same underlying model. Learn when to use the simpler approach and when regression's flexibility is worth it.

Quick Hits

- •T-tests, ANOVA, and regression are all special cases of the general linear model

- •A two-sample t-test is regression with one binary predictor

- •One-way ANOVA is regression with one categorical predictor (dummy coded)

- •Use the simpler tool when it suffices - it's more interpretable

- •Use regression when you need: continuous predictors, multiple covariates, or interactions

TL;DR

T-tests, ANOVA, and linear regression are all special cases of the general linear model. A two-sample t-test is regression with one binary predictor. One-way ANOVA is regression with one categorical predictor. Understanding this unification helps you see that the "choice" between them is about presentation, not statistics. Use the simpler tool when it fits your problem; switch to regression when you need continuous predictors, covariates, or complex comparisons.

The Big Picture

All these tests fit the same underlying model:

Where:

- Y is your outcome

- X is your design matrix (encodes groups/predictors)

- is your coefficients (means or effects)

- ε is error (assumed normal, constant variance)

The "choice" between tests is really about:

- How you construct X (dummy coding, effect coding, etc.)

- How you report results (means vs. coefficients, F vs. t)

- How interpretable the output is for your audience

One-Sample t-Test = Regression with Intercept Only

The t-Test

Test whether mean differs from a value (usually 0):

The Regression

is the mean of . Testing is identical to the one-sample t-test.

Demonstration

import numpy as np

from scipy import stats

import statsmodels.formula.api as smf

import pandas as pd

np.random.seed(42)

y = np.random.normal(5, 2, 100)

# One-sample t-test

t_stat, p_value = stats.ttest_1samp(y, 0)

print(f"T-test: t = {t_stat:.4f}, p = {p_value:.4f}")

# Regression (intercept only)

data = pd.DataFrame({'y': y})

model = smf.ols('y ~ 1', data=data).fit()

print(f"Regression: t = {model.tvalues['Intercept']:.4f}, p = {model.pvalues['Intercept']:.4f}")

print(f"Coefficient (mean) = {model.params['Intercept']:.4f}, Sample mean = {y.mean():.4f}")

Output:

T-test: t = 24.8503, p = 0.0000

Regression: t = 24.8503, p = 0.0000

Coefficient (mean) = 4.9397, Sample mean = 4.9397

Two-Sample t-Test = Regression with Binary Predictor

The t-Test

Compare means of two groups:

The Regression

Where Group = 0 for control, 1 for treatment.

Interpretation:

- = mean of control group (when Group = 0)

- = difference in means (treatment - control)

- Testing is identical to the two-sample t-test

Demonstration

# Generate data

np.random.seed(42)

control = np.random.normal(10, 3, 50)

treatment = np.random.normal(12, 3, 50)

# Two-sample t-test (equal variance)

t_stat, p_value = stats.ttest_ind(control, treatment)

print(f"T-test: t = {t_stat:.4f}, p = {p_value:.4f}")

# Regression

data = pd.DataFrame({

'y': np.concatenate([control, treatment]),

'group': [0]*50 + [1]*50

})

model = smf.ols('y ~ group', data=data).fit()

print(f"Regression: t = {model.tvalues['group']:.4f}, p = {model.pvalues['group']:.4f}")

print(f"\nControl mean: {control.mean():.4f}")

print(f"Intercept (β₀): {model.params['Intercept']:.4f}")

print(f"Difference: {treatment.mean() - control.mean():.4f}")

print(f"Group coefficient (β₁): {model.params['group']:.4f}")

Note: The equal-variance t-test matches regression. Welch's t-test (unequal variance) requires heteroscedasticity-robust standard errors in regression.

One-Way ANOVA = Regression with Categorical Predictor

ANOVA

Compare means across k groups:

Regression with Dummy Variables

For k groups, create k-1 dummy variables:

Interpretation:

- = mean of reference group

- = difference between group j and reference group

The F-Test Connection

ANOVA reports an F-statistic testing all groups equal. In regression:

- The overall F-test for the model tests the same hypothesis

- Individual t-tests for dummy coefficients test pairwise differences from reference

Demonstration

# Three groups

np.random.seed(42)

group_a = np.random.normal(10, 2, 40)

group_b = np.random.normal(12, 2, 40)

group_c = np.random.normal(11, 2, 40)

# One-way ANOVA

f_stat, p_value = stats.f_oneway(group_a, group_b, group_c)

print(f"ANOVA: F = {f_stat:.4f}, p = {p_value:.4f}")

# Regression with dummies

data = pd.DataFrame({

'y': np.concatenate([group_a, group_b, group_c]),

'group': ['A']*40 + ['B']*40 + ['C']*40

})

model = smf.ols('y ~ C(group)', data=data).fit()

print(f"Regression F-test: F = {model.fvalue:.4f}, p = {model.f_pvalue:.4f}")

print("\nGroup means:")

print(f" A: {group_a.mean():.4f}")

print(f" B: {group_b.mean():.4f}")

print(f" C: {group_c.mean():.4f}")

print("\nRegression coefficients:")

print(f" Intercept (Group A mean): {model.params['Intercept']:.4f}")

print(f" B vs A: {model.params['C(group)[T.B]']:.4f}")

print(f" C vs A: {model.params['C(group)[T.C]']:.4f}")

Two-Way ANOVA = Regression with Two Categorical Predictors

Two-Way ANOVA

Tests:

- Main effect of Factor A

- Main effect of Factor B

- A × B Interaction

Regression Equivalent

With appropriate dummy coding for categorical variables.

# Regression for two-way ANOVA

model = smf.ols('y ~ C(factor_a) * C(factor_b)', data=data).fit()

# ANOVA table from regression

import statsmodels.api as sm

anova_table = sm.stats.anova_lm(model, typ=2) # Type II SS

print(anova_table)

Paired t-Test = Regression on Differences

Paired t-Test

Compare paired observations (before/after, matched pairs):

Regression Equivalent

Create difference variable, then one-sample test:

Testing is the paired t-test.

Alternative: Repeated Measures Regression

# Mixed effects model approach

import statsmodels.formula.api as smf

# Long format data with subject ID

model = smf.mixedlm('y ~ time', data=data, groups=data['subject_id']).fit()

The Equivalence Table

| Simple Test | Regression Equivalent |

|---|---|

| One-sample t-test | Y ~ 1 (intercept only) |

| Two-sample t-test | Y ~ group (binary) |

| Paired t-test | Y_diff ~ 1 or mixed model |

| One-way ANOVA | Y ~ factor (dummy coded) |

| Two-way ANOVA | Y ~ A * B |

| ANCOVA | Y ~ factor + covariate |

| Correlation test | Y ~ X (standardized) |

| Simple regression | Y ~ X |

| Multiple regression | Y ~ X1 + X2 + ... |

Code: Demonstrating Equivalence

Python

import numpy as np

import pandas as pd

from scipy import stats

import statsmodels.formula.api as smf

import statsmodels.api as sm

np.random.seed(42)

# --- Two-sample t-test vs regression ---

control = np.random.normal(100, 15, 50)

treatment = np.random.normal(110, 15, 50)

# T-test

t_result = stats.ttest_ind(control, treatment)

# Equivalent regression

data = pd.DataFrame({

'y': np.concatenate([control, treatment]),

'group': [0]*50 + [1]*50

})

model = smf.ols('y ~ group', data=data).fit()

The t-test and regression produce the same t-statistic and p-value. The regression coefficient equals the mean difference between groups.

# --- One-way ANOVA vs regression ---

group_a = np.random.normal(100, 15, 40)

group_b = np.random.normal(110, 15, 40)

group_c = np.random.normal(105, 15, 40)

# ANOVA

f_result = stats.f_oneway(group_a, group_b, group_c)

# Equivalent regression

data = pd.DataFrame({

'y': np.concatenate([group_a, group_b, group_c]),

'group': ['A']*40 + ['B']*40 + ['C']*40

})

model = smf.ols('y ~ C(group)', data=data).fit()

The F-statistic and p-value are identical from both approaches. ANOVA is just regression with categorical predictors.

# --- Paired t-test vs regression on differences ---

before = np.random.normal(100, 15, 30)

after = before + np.random.normal(5, 10, 30)

# Paired t-test

t_result = stats.ttest_rel(before, after)

# Equivalent regression on differences

diff = after - before

data = pd.DataFrame({'diff': diff})

model = smf.ols('diff ~ 1', data=data).fit()

A paired t-test is equivalent to testing whether the intercept of a regression on differences is zero. Same t-statistic, same p-value.

R

library(tidyverse)

demonstrate_equivalence <- function() {

set.seed(42)

# Two-sample case

cat(strrep("=", 60), "\n")

cat("TWO-SAMPLE T-TEST vs REGRESSION\n")

cat(strrep("=", 60), "\n")

control <- rnorm(50, 100, 15)

treatment <- rnorm(50, 110, 15)

# T-test

t_result <- t.test(control, treatment, var.equal = TRUE)

cat(sprintf("\nTwo-sample t-test:\n"))

cat(sprintf(" t = %.4f\n", t_result$statistic))

cat(sprintf(" p = %.4f\n", t_result$p.value))

# Regression

data <- tibble(

y = c(control, treatment),

group = factor(c(rep(0, 50), rep(1, 50)))

)

model <- lm(y ~ group, data = data)

cat(sprintf("\nRegression:\n"))

cat(sprintf(" t = %.4f\n", summary(model)$coefficients["group1", "t value"]))

cat(sprintf(" p = %.4f\n", summary(model)$coefficients["group1", "Pr(>|t|)"]))

# One-way ANOVA case

cat("\n", strrep("=", 60), "\n")

cat("ONE-WAY ANOVA vs REGRESSION\n")

cat(strrep("=", 60), "\n")

group_a <- rnorm(40, 100, 15)

group_b <- rnorm(40, 110, 15)

group_c <- rnorm(40, 105, 15)

data <- tibble(

y = c(group_a, group_b, group_c),

group = factor(c(rep("A", 40), rep("B", 40), rep("C", 40)))

)

# ANOVA

aov_result <- aov(y ~ group, data = data)

cat(sprintf("\nOne-way ANOVA:\n"))

cat(sprintf(" F = %.4f\n", summary(aov_result)[[1]]["group", "F value"]))

cat(sprintf(" p = %.4f\n", summary(aov_result)[[1]]["group", "Pr(>F)"]))

# Regression

model <- lm(y ~ group, data = data)

cat(sprintf("\nRegression:\n"))

cat(sprintf(" F = %.4f\n", summary(model)$fstatistic[1]))

cat(sprintf(" p = %.4f\n", pf(summary(model)$fstatistic[1],

summary(model)$fstatistic[2],

summary(model)$fstatistic[3],

lower.tail = FALSE)))

}

demonstrate_equivalence()

When to Use Which

Use t-Test When

- You have two groups

- No covariates to control for

- You want simple, recognizable output

- Your audience thinks in terms of "comparing two means"

Use ANOVA When

- You have multiple (3+) categorical groups

- No continuous predictors

- You want to decompose variance (between vs. within)

- Your audience is familiar with ANOVA tables

Use Regression When

- You have continuous predictors

- You need to control for covariates

- You want custom contrasts (not just vs. reference)

- You have complex interactions

- You need to include both categorical and continuous predictors

- You want coefficient-based interpretation

Advantages of the Regression Framing

1. Flexibility

Regression handles any combination of:

- Continuous predictors

- Categorical predictors (with dummy coding)

- Interactions

- Covariates

2. Custom Contrasts

With regression, you can easily test specific comparisons:

# Test: Is the average of B and C different from A?

model = smf.ols('y ~ C(group, Treatment("A"))', data=data).fit()

# Custom contrast matrix

from patsy.contrasts import ContrastMatrix

# ... define specific contrasts

3. Extends to GLMs

The same framework extends to:

- Logistic regression (binary outcomes)

- Poisson regression (count outcomes)

- Any generalized linear model

4. Clearer About What You're Testing

Regression output shows exactly what comparison each coefficient represents, rather than hiding it in sum-of-squares decomposition.

Common Misconceptions

"Regression requires normality of X"

False. Regression assumes normality of residuals (errors), not predictors. You can use regression with any distribution of X.

"ANOVA is for experiments, regression is for observational data"

False. Both can be used for either. The model is the same; the interpretation differs based on study design.

"I need to check normality of my groups for ANOVA"

Partially false. You need approximate normality of residuals (within each group). With large samples, this matters less due to CLT.

"T-tests are less powerful than regression"

False. They're identical (same test). Regression might have more power if you include relevant covariates that reduce error variance.

Related Methods

- Regression for Analysts (Pillar) - Complete regression framework

- One-Way ANOVA - ANOVA details

- Welch's t-Test vs. Student's t-Test - Which t-test to use

- Interaction Terms - Factorial designs in regression

Key Takeaway

T-tests, ANOVA, and regression are all the general linear model with different interfaces. Understanding this unification demystifies statistical testing: there's one underlying framework, and the "different tests" are just different ways of specifying and presenting it. Use the simplest tool that fits your problem (t-test for two groups, ANOVA for multiple groups with categorical predictors), but know that regression is there when you need its flexibility (continuous predictors, covariates, custom contrasts). The p-values and statistical conclusions will be identical.

References

- https://lindeloev.github.io/tests-as-linear/

- https://www.amazon.com/Statistical-Rethinking-Bayesian-Examples-Chapman/dp/036713991X

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0022103117307746

- Lindeløv, J. K. (2019). Common statistical tests are linear models. Online tutorial.

- McElreath, R. (2020). Statistical rethinking: A Bayesian course with examples in R and Stan (2nd ed.). CRC Press.

- Judd, C. M., McClelland, G. H., & Ryan, C. S. (2017). Data analysis: A model comparison approach (3rd ed.). Routledge.

Frequently Asked Questions

Will I get different results from a t-test vs. regression?

Why would I use ANOVA if it's just regression?

When should I switch from ANOVA to regression?

Key Takeaway

T-tests, ANOVA, and regression are all the general linear model with different packaging. Understanding this unification helps you see when the simpler tool suffices (categorical predictors, no covariates) and when regression's flexibility is needed (continuous predictors, multiple controls, custom contrasts).