Contents

Collinearity: When It Breaks Interpretation and What to Do

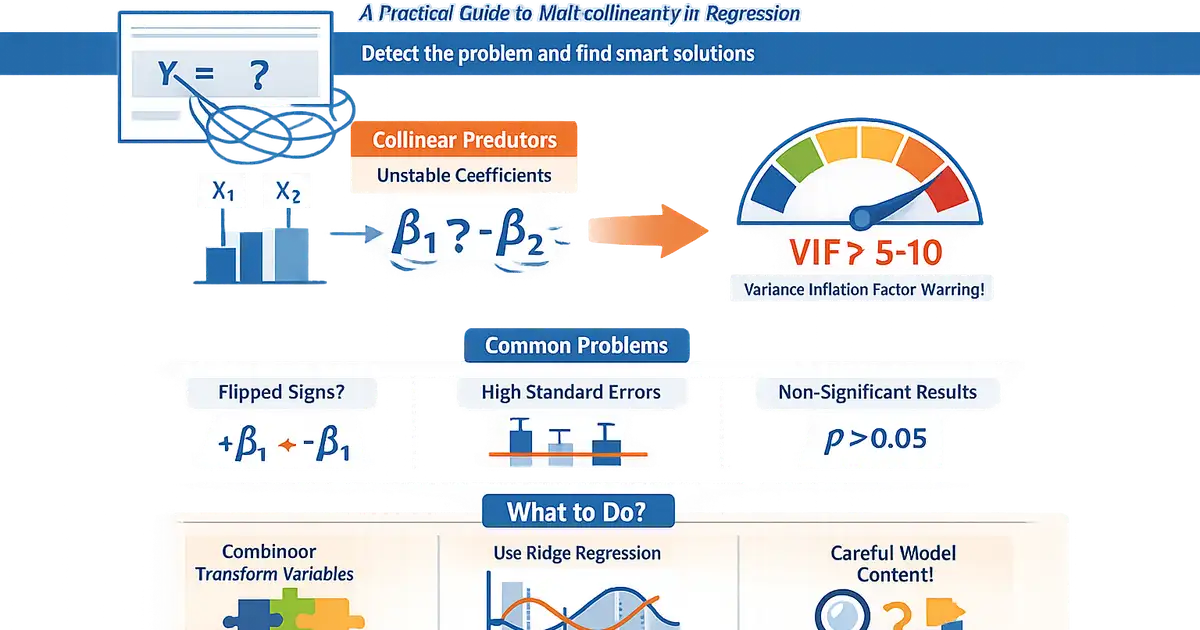

A practical guide to multicollinearity in regression. Learn when collinearity is a problem, how to detect it, and practical solutions that don't involve blindly dropping variables.

Quick Hits

- •Collinearity = correlated predictors → unstable coefficient estimates

- •VIF > 5-10 signals potential problems (but context matters)

- •Coefficients may flip sign or become non-significant - not because of bad data, but because they're poorly identified

- •Perfect collinearity is detectable (model fails); high collinearity is harder

- •Solutions depend on your goal: prediction doesn't care, interpretation does

TL;DR

Multicollinearity occurs when predictor variables are highly correlated. It doesn't bias coefficients, but it inflates standard errors, making individual predictors hard to interpret. VIF > 5-10 signals problems. Solutions include combining variables, ridge regression, or simply accepting that correlated effects can't be separated. The key insight: collinearity is a problem for interpretation, not prediction.

What Is Collinearity?

Definition

Multicollinearity occurs when predictor variables in a regression model are correlated with each other. This creates problems because the model can't distinguish the individual effects.

Perfect Collinearity

If one predictor is a perfect linear function of others:

- X₃ = 2X₁ + 5X₂

The model cannot be fit. Software will drop a variable or throw an error.

Common cause: Including a dummy variable for all categories (the "dummy variable trap").

High Collinearity

More common and more insidious: predictors are highly but not perfectly correlated.

- Age and years of experience

- Revenue and customer count

- Multiple survey items measuring the same construct

Why Collinearity Is a Problem

The Core Issue

When X₁ and X₂ are highly correlated, the model can't tell which one is "responsible" for the effect.

Extreme example: X₁ and X₂ are nearly identical

- Model could attribute the effect to X₁ and not X₂

- Or to X₂ and not X₁

- Or split between them in any way

What Happens to Estimates

| Aspect | Effect of Collinearity |

|---|---|

| Coefficient estimates | Unbiased (still correct on average) |

| Standard errors | Inflated (often dramatically) |

| t-statistics | Reduced (harder to find significance) |

| Coefficient stability | Unstable (small data changes → big coefficient changes) |

| Signs | May flip (positive becomes negative) |

| Overall R² | Usually unaffected |

| Predictions | Usually unaffected |

The Paradox

You might see:

- High overall R² (model explains a lot)

- None of the individual coefficients significant

- Coefficients with "wrong" signs

This isn't a contradiction—the predictors together explain the outcome, but the model can't attribute credit to individuals.

Detecting Collinearity

Method 1: Correlation Matrix

Look for high pairwise correlations (r > 0.7-0.8).

Limitation: Misses multiway collinearity (X₃ is a linear combination of X₁ and X₂, even if no pair is highly correlated).

Method 2: Variance Inflation Factor (VIF)

VIF measures how much the variance of a coefficient is inflated due to collinearity.

Where is the R² from regressing predictor on all other predictors.

Interpretation:

- VIF = 1: No collinearity

- VIF = 5: Variance is 5× what it would be without collinearity

- VIF = 10: Standard error is larger

Thresholds (rules of thumb):

- VIF > 5: Moderate concern

- VIF > 10: Serious concern

- VIF > 100: Near-perfect collinearity

Method 3: Condition Number

The condition number of the predictor matrix is another diagnostic.

-

30: Serious collinearity

Method 4: Symptoms

Watch for these signs:

- Coefficients change dramatically when adding/removing variables

- Coefficients have opposite signs from bivariate correlations

- High R² but no significant individual predictors

- Very large standard errors

Code: Detecting Collinearity

Python

import numpy as np

import pandas as pd

import statsmodels.api as sm

import statsmodels.formula.api as smf

from statsmodels.stats.outliers_influence import variance_inflation_factor

def check_collinearity(model):

"""

Comprehensive collinearity diagnostics.

Parameters:

-----------

model : statsmodels RegressionResults

Fitted OLS model

Returns:

--------

dict with diagnostics

"""

results = {}

# Get predictor matrix (excluding intercept for VIF)

X = model.model.exog

feature_names = model.model.exog_names

# Correlation matrix (excluding intercept)

if 'Intercept' in feature_names or 'const' in feature_names:

X_no_const = X[:, 1:]

names_no_const = [n for n in feature_names if n not in ['Intercept', 'const']]

else:

X_no_const = X

names_no_const = feature_names

corr_matrix = pd.DataFrame(

np.corrcoef(X_no_const.T),

columns=names_no_const,

index=names_no_const

)

results['correlation_matrix'] = corr_matrix

# High correlations

high_corr = []

for i, var1 in enumerate(names_no_const):

for j, var2 in enumerate(names_no_const):

if i < j and abs(corr_matrix.iloc[i, j]) > 0.7:

high_corr.append({

'var1': var1,

'var2': var2,

'correlation': corr_matrix.iloc[i, j]

})

results['high_correlations'] = pd.DataFrame(high_corr)

# VIF

vif_data = []

for i, name in enumerate(feature_names):

vif = variance_inflation_factor(X, i)

vif_data.append({'Variable': name, 'VIF': vif})

vif_df = pd.DataFrame(vif_data)

results['vif'] = vif_df

# Flag problematic variables

results['high_vif_variables'] = vif_df[vif_df['VIF'] > 5]['Variable'].tolist()

if 'Intercept' in results['high_vif_variables']:

results['high_vif_variables'].remove('Intercept')

if 'const' in results['high_vif_variables']:

results['high_vif_variables'].remove('const')

# Condition number

results['condition_number'] = np.linalg.cond(X)

# Summary flags

results['has_collinearity_issues'] = (

len(results['high_vif_variables']) > 0 or

results['condition_number'] > 30

)

return results

def compare_coefficient_stability(data, formula, drop_vars):

"""

Check how coefficients change when dropping variables.

Helps identify which variables are causing instability.

"""

# Full model

full_model = smf.ols(formula, data=data).fit()

comparisons = [{'Model': 'Full', **dict(zip(full_model.params.index, full_model.params.values))}]

# Models dropping each variable

for var in drop_vars:

reduced_formula = formula.replace(f' + {var}', '').replace(f'{var} + ', '')

if var in reduced_formula:

reduced_formula = reduced_formula.replace(var, '').replace(' ~ +', ' ~').replace('+ +', '+')

try:

reduced_model = smf.ols(reduced_formula, data=data).fit()

row = {'Model': f'Drop {var}'}

for param in full_model.params.index:

if param in reduced_model.params.index:

row[param] = reduced_model.params[param]

else:

row[param] = np.nan

comparisons.append(row)

except:

pass

return pd.DataFrame(comparisons)

# Example

if __name__ == "__main__":

np.random.seed(42)

n = 200

# Create data with collinearity

x1 = np.random.normal(0, 1, n)

x2 = x1 + np.random.normal(0, 0.3, n) # Highly correlated with x1

x3 = np.random.normal(0, 1, n) # Independent

y = 2 + 3*x1 + 2*x2 + 1*x3 + np.random.normal(0, 1, n)

data = pd.DataFrame({'y': y, 'x1': x1, 'x2': x2, 'x3': x3})

# Fit model

model = smf.ols('y ~ x1 + x2 + x3', data=data).fit()

print("Model Summary")

print("=" * 50)

print(model.summary().tables[1])

print("\n" + "=" * 50)

print("Collinearity Diagnostics")

diagnostics = check_collinearity(model)

print("\nVIF:")

print(diagnostics['vif'].to_string(index=False))

print(f"\nCondition Number: {diagnostics['condition_number']:.1f}")

print(f"\nHigh VIF Variables: {diagnostics['high_vif_variables']}")

if len(diagnostics['high_correlations']) > 0:

print("\nHigh Correlations:")

print(diagnostics['high_correlations'].to_string(index=False))

R

library(tidyverse)

library(car) # For VIF

check_collinearity <- function(model) {

#' Comprehensive collinearity diagnostics

# VIF

vif_values <- vif(model)

vif_df <- tibble(

Variable = names(vif_values),

VIF = as.numeric(vif_values)

)

# Correlation matrix of predictors

X <- model.matrix(model)[, -1] # Exclude intercept

corr_matrix <- cor(X)

# Find high correlations

high_corr <- which(abs(corr_matrix) > 0.7 & corr_matrix != 1, arr.ind = TRUE)

high_corr_pairs <- if (nrow(high_corr) > 0) {

data.frame(

var1 = rownames(corr_matrix)[high_corr[, 1]],

var2 = colnames(corr_matrix)[high_corr[, 2]],

correlation = corr_matrix[high_corr]

) %>%

filter(as.character(var1) < as.character(var2))

} else {

data.frame(var1 = character(), var2 = character(), correlation = numeric())

}

# Condition number

condition_num <- kappa(X, exact = TRUE)

list(

vif = vif_df,

correlation_matrix = corr_matrix,

high_correlations = high_corr_pairs,

condition_number = condition_num,

high_vif_variables = vif_df$Variable[vif_df$VIF > 5],

has_issues = any(vif_df$VIF > 5) | condition_num > 30

)

}

# Example

set.seed(42)

n <- 200

data <- tibble(

x1 = rnorm(n),

x2 = x1 + rnorm(n, 0, 0.3), # Correlated with x1

x3 = rnorm(n)

) %>%

mutate(y = 2 + 3*x1 + 2*x2 + 1*x3 + rnorm(n))

model <- lm(y ~ x1 + x2 + x3, data = data)

cat("Model Summary\n")

cat(strrep("=", 50), "\n")

print(summary(model))

cat("\nCollinearity Diagnostics\n")

cat(strrep("=", 50), "\n")

diagnostics <- check_collinearity(model)

cat("\nVIF:\n")

print(diagnostics$vif)

cat(sprintf("\nCondition Number: %.1f\n", diagnostics$condition_number))

cat(sprintf("High VIF Variables: %s\n", paste(diagnostics$high_vif_variables, collapse = ", ")))

Solutions for Collinearity

Solution 1: Do Nothing (Seriously)

When appropriate:

- Your goal is prediction, not coefficient interpretation

- The collinear variables are controls, not your focus

- You accept that these effects can't be separated

Why it's valid: Predictions are still good; R² is unaffected.

Solution 2: Combine Variables

If X₁ and X₂ measure the same underlying thing, combine them:

# Average

data['combined'] = (data['x1'] + data['x2']) / 2

# PCA

from sklearn.decomposition import PCA

pca = PCA(n_components=1)

data['pc1'] = pca.fit_transform(data[['x1', 'x2']])

# Factor analysis

# If you have multiple indicators of the same construct

When appropriate:

- Variables conceptually measure the same thing

- You don't need to separate their effects

Solution 3: Drop One Variable

When appropriate:

- One variable is clearly redundant

- You have strong theoretical reason to prefer one

- Sensitivity analysis shows results are robust

Caution: Dropping a variable that belongs in the model creates omitted variable bias. Don't drop just because of high VIF.

Solution 4: Ridge Regression

Ridge regression adds a penalty that shrinks coefficients, stabilizing them under collinearity.

from sklearn.linear_model import Ridge, RidgeCV

# Cross-validated ridge

ridge_cv = RidgeCV(alphas=[0.01, 0.1, 1, 10, 100])

ridge_cv.fit(X, y)

print(f"Best alpha: {ridge_cv.alpha_}")

print(f"Coefficients: {ridge_cv.coef_}")

Trade-off: Coefficients are biased toward zero but more stable. Predictions often improve.

Solution 5: Get More Data

More data reduces variance of all estimates, partially mitigating collinearity issues.

Limitation: Doesn't help if collinearity is inherent (age and experience will always correlate).

Solution 6: Center Predictors

Centering reduces collinearity involving interactions:

data['x1_centered'] = data['x1'] - data['x1'].mean()

data['x2_centered'] = data['x2'] - data['x2'].mean()

Limitation: Only helps with certain types of collinearity (especially with polynomial/interaction terms).

Solution Decision Framework

START: High VIF or collinearity detected

↓

QUESTION: Is your goal prediction or interpretation?

├── Prediction → Likely OK to proceed (check prediction accuracy)

└── Interpretation → Continue

↓

QUESTION: Are collinear variables your focus or controls?

├── Controls → Likely OK if main variables are fine

└── Focus variables → Continue

↓

QUESTION: Do collinear variables measure the same construct?

├── Yes → Combine them (average, PCA, factor analysis)

└── No → Continue

↓

QUESTION: Is one variable clearly more important theoretically?

├── Yes → Consider dropping the other (with sensitivity check)

└── No → Continue

↓

CONSIDER:

- Ridge regression (biased but stable)

- Accept that effects can't be separated

- Report partial effects and total effect of combined variables

When Collinearity Isn't a Problem

For Prediction

Collinearity doesn't hurt prediction. If your goal is forecasting or risk scoring, high VIF may not matter.

For Categorical Variables

Dummy variables for a categorical variable will be correlated (choosing Category B means not choosing Category A). This is fine—VIF among dummies is expected.

Don't drop dummies to reduce VIF—that changes your reference category interpretation.

For Interaction Terms

Main effects and interactions are often correlated. This is expected:

x1, x2, x1*x2 → VIF will be high for interaction

Solution: Center the main effects before creating interactions. Reduces VIF without changing interpretation.

For Polynomial Terms

x and x² are correlated by construction.

Solution: Use orthogonal polynomials or center x before squaring.

Common Mistakes

Mistake 1: Automatically Dropping High-VIF Variables

Wrong: "VIF > 10, so I dropped x2"

Problem: If x2 belongs in the model, dropping it creates omitted variable bias. Now your other coefficients are wrong.

Better: Consider why these variables are correlated and whether you need to separate them.

Mistake 2: Using VIF Threshold Blindly

Wrong: "All VIFs are below 10, so no collinearity problem"

Problem: VIF thresholds are arbitrary. VIF = 9 might still cause issues; VIF = 12 might be acceptable for control variables.

Better: Consider the context and your interpretive goals.

Mistake 3: Ignoring Collinearity When Interpreting

Wrong: "The coefficient on x1 is 5 and significant"

Problem: If x1 and x2 are collinear, the coefficient on x1 is conditional on holding x2 constant—but x1 and x2 move together in reality.

Better: Acknowledge that these effects can't be cleanly separated.

Mistake 4: Blaming Collinearity for Everything

Wrong: "Results don't make sense—must be collinearity"

Reality: Collinearity causes high variance, not bias. If coefficients have wrong signs, it might be:

- Normal variance (check CIs—do they include "correct" values?)

- Model misspecification

- Confounding

Related Methods

- Regression for Analysts (Pillar) - Complete regression framework

- Linear Regression Diagnostics - Other diagnostics

- Feature Scaling and Transforms - Centering to reduce collinearity

- Interaction Terms - Managing interaction collinearity

Key Takeaway

Collinearity makes individual coefficients hard to interpret because correlated predictors "share credit" for explaining the outcome. Coefficients become unstable with inflated standard errors, but predictions remain valid. Before dropping variables (which risks omitted variable bias), consider whether you truly need to separate these effects. Combining variables, ridge regression, or simply acknowledging the limitation may be better than creating new problems by dropping important predictors.

References

- https://www.jstor.org/stable/2685573

- https://journalofbigdata.springeropen.com/articles/10.1186/s40537-019-0252-9

- https://online.stat.psu.edu/stat462/node/177/

- Belsley, D. A., Kuh, E., & Welsch, R. E. (1980). Regression diagnostics: Identifying influential data and sources of collinearity. Wiley.

- O'Brien, R. M. (2007). A caution regarding rules of thumb for variance inflation factors. *Quality & Quantity*, 41(5), 673-690.

- Penn State STAT 462. Lesson 12: Multicollinearity. Online course materials.

Frequently Asked Questions

Does collinearity bias my coefficient estimates?

What VIF threshold should I use?

Should I just drop the correlated variable?

Key Takeaway

Collinearity makes individual coefficients hard to interpret, but overall predictions may still be fine. Check VIF, but don't blindly drop variables—that can introduce bias. Consider whether you truly need to separate the correlated effects, or whether a combined measure or dimension reduction makes more sense.