Contents

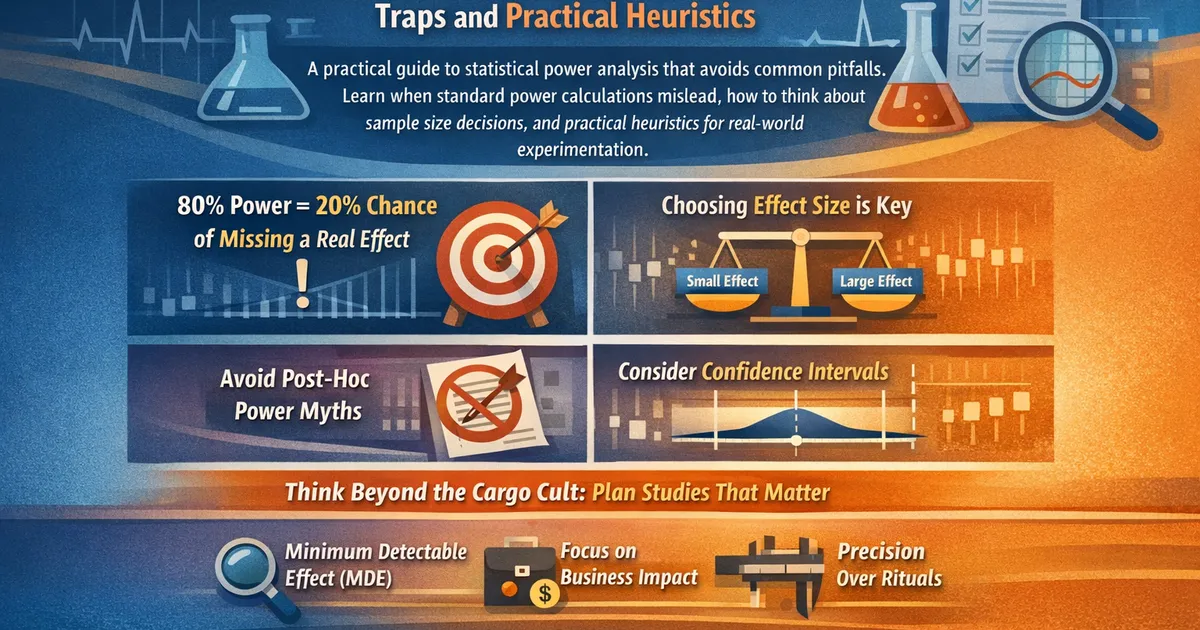

Power Analysis Without Cargo Culting: Traps and Practical Heuristics

A practical guide to statistical power analysis that avoids common pitfalls. Learn when standard power calculations mislead, how to think about sample size decisions, and practical heuristics for real-world experimentation.

Quick Hits

- •Power = probability of detecting an effect that actually exists

- •80% power means 20% chance of missing a real effect - that's often too high

- •The hardest part is choosing the effect size - everything else is arithmetic

- •Post-hoc power analysis is meaningless - don't do it

- •Consider precision (CI width) as an alternative planning framework

TL;DR

Power analysis helps you determine sample sizes needed to detect effects of a given size. But standard power calculations are often cargo-culted—performed ritualistically without understanding what they mean. The critical input is choosing an effect size that matters for your decision, not using conventions like "small effect = 0.2." Post-hoc power is meaningless. Consider precision-based planning as an alternative. This article provides practical guidance for sample size decisions in real experiments.

What Power Actually Means

Statistical power is the probability of detecting an effect when one truly exists.

If your experiment has 80% power:

- There's an 80% chance you'll get if the true effect is at least as large as your assumed effect size

- There's a 20% chance you'll "miss" the effect (Type II error / false negative)

The power equation has four connected parameters:

- Effect size: How big is the true effect?

- Sample size: How many observations?

- level: Your false positive threshold (usually 0.05)

- Power: Your target true positive rate (usually 0.80)

Fix any three, and the fourth is determined.

The Core Problem: Choosing Effect Size

Power calculations are straightforward arithmetic. The hard part—and where most analyses go wrong—is choosing the effect size to plan for.

Bad Approach: Cohen's Conventions

Cohen (1988) suggested "small" (d=0.2), "medium" (d=0.5), and "large" (d=0.8) effect sizes. These were meant as rough guidelines when you have no domain knowledge.

Why this fails:

- A d=0.2 effect on revenue might be worth millions

- A d=0.5 effect on a vanity metric might be worthless

- Effect sizes don't come labeled—you need to define what matters

Better Approach: Minimum Detectable Effect (MDE)

Instead of asking "what effect do I expect?", ask:

"What's the smallest effect that would change my decision?"

This is your MDE—the practical significance threshold below which you wouldn't take action anyway.

Example:

- Implementing the feature costs $500K in engineering time

- Need at least $600K annual revenue lift to justify

- Current revenue: $10M

- MDE: 6% revenue increase

- Plan your experiment to detect 6% with high confidence

Common Power Analysis Traps

Trap 1: Using Expected Effect Size

Mistake: "We expect a 10% lift, so we'll power for 10%"

Problem: If you're wrong about your expectation, you won't detect smaller real effects.

Fix: Power for the smallest effect worth detecting, not your best guess of what will happen.

Trap 2: Post-Hoc Power Analysis

Mistake: After a non-significant result, calculating "we only had 30% power"

Problem: Post-hoc power is a deterministic function of your p-value. If , observed power is always ~50%. It adds zero information.

What post-hoc power tells you:

- If p is high, observed power is low

- If p is low, observed power is high

- This is mathematical tautology, not insight

Fix: Report confidence intervals instead. "We can rule out effects larger than X."

# Post-hoc power is meaningless - here's why

import scipy.stats as stats

# If you observe p = 0.05 (z = 1.96)

# Observed power at that exact effect size is always ~50%

z_crit = 1.96

observed_power = 1 - stats.norm.cdf(z_crit - z_crit) # Always 0.5

Trap 3: Treating 80% as Sacred

Mistake: Always using 80% power because it's conventional.

Problem: 80% power = 20% miss rate. For important decisions, that's often too high.

Consider:

- High-stakes decision → 90-95% power

- Exploratory analysis → 80% may be fine

- Expensive intervention → power for practical significance threshold, not just statistical

Trap 4: Ignoring Precision

Mistake: Only thinking about statistical significance, not estimation precision.

Problem: You might detect an effect is non-zero without knowing if it's meaningful.

Fix: Plan for confidence interval width, not just .

Trap 5: One-Time Calculation

Mistake: Running power analysis once before the experiment and never revisiting.

Problem: Real experiments have noise, dropouts, and surprises.

Fix: Monitor effective sample size during the experiment. Build in buffer (10-20% extra).

Practical Power Analysis

Step 1: Define Your MDE in Business Terms

Ask:

- What decision will this experiment inform?

- What's the cost of implementing vs. not implementing?

- Below what effect size would we not take action?

Example calculation:

Implementation cost: $200K

Required ROI: 2x in first year

Annual baseline: $5M revenue

MDE needed: $400K / $5M = 8% revenue lift

Step 2: Convert to Standardized Effect Size (If Needed)

For comparing means, Cohen's d relates to your raw effect:

Example:

- MDE: 5% lift on a metric with mean=100

- Raw MDE: 5 units

- Historical SD: 25 units

- d = 5/25 = 0.2

Step 3: Calculate Sample Size

For a two-sample t-test at :

| Power | Sample per group (d=0.2) | d=0.5 | d=0.8 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 80% | 393 | 64 | 26 |

| 90% | 527 | 86 | 34 |

| 95% | 651 | 105 | 42 |

Step 4: Reality Check

- Can you actually get this sample?

- How long will it take?

- Is the experiment worth running at this sample size?

- What happens if the true effect is half your MDE?

Code: Power Analysis

Python

import numpy as np

from scipy import stats

from statsmodels.stats.power import TTestIndPower, NormalIndPower

def sample_size_for_means(

mde: float,

baseline_sd: float,

alpha: float = 0.05,

power: float = 0.80,

ratio: float = 1.0

) -> dict:

"""

Calculate sample size needed to detect a difference in means.

Parameters:

-----------

mde : float

Minimum detectable effect in raw units

baseline_sd : float

Standard deviation of the metric

alpha : float

Significance level (default 0.05)

power : float

Desired power (default 0.80)

ratio : float

Ratio of treatment to control size (default 1.0 = equal)

Returns:

--------

dict with sample sizes and effect size

"""

effect_size = mde / baseline_sd # Cohen's d

analysis = TTestIndPower()

n_per_group = analysis.solve_power(

effect_size=effect_size,

alpha=alpha,

power=power,

ratio=ratio,

alternative='two-sided'

)

return {

'effect_size_d': effect_size,

'n_control': int(np.ceil(n_per_group)),

'n_treatment': int(np.ceil(n_per_group * ratio)),

'n_total': int(np.ceil(n_per_group * (1 + ratio))),

'power': power,

'alpha': alpha

}

def sample_size_for_proportions(

baseline_rate: float,

mde_absolute: float,

alpha: float = 0.05,

power: float = 0.80

) -> dict:

"""

Calculate sample size for detecting a difference in proportions.

Parameters:

-----------

baseline_rate : float

Current conversion rate (e.g., 0.05 for 5%)

mde_absolute : float

Minimum detectable effect in absolute terms (e.g., 0.01 for 1pp)

alpha : float

Significance level

power : float

Desired power

Returns:

--------

dict with sample sizes

"""

p1 = baseline_rate

p2 = baseline_rate + mde_absolute

# Effect size for proportions (Cohen's h)

h = 2 * np.arcsin(np.sqrt(p2)) - 2 * np.arcsin(np.sqrt(p1))

analysis = NormalIndPower()

n_per_group = analysis.solve_power(

effect_size=h,

alpha=alpha,

power=power,

alternative='two-sided'

)

return {

'baseline_rate': p1,

'target_rate': p2,

'mde_relative': (p2 - p1) / p1 * 100,

'effect_size_h': h,

'n_per_group': int(np.ceil(n_per_group)),

'n_total': int(np.ceil(n_per_group * 2)),

'power': power,

'alpha': alpha

}

def power_curve(

baseline_sd: float,

n_per_group: int,

alpha: float = 0.05,

effect_sizes: np.ndarray = None

) -> dict:

"""

Calculate power across a range of effect sizes.

Useful for understanding sensitivity of your design.

"""

if effect_sizes is None:

effect_sizes = np.linspace(0.05, 1.0, 20)

analysis = TTestIndPower()

powers = [

analysis.power(effect_size=d, nobs1=n_per_group, alpha=alpha, ratio=1.0)

for d in effect_sizes

]

return {

'effect_sizes': effect_sizes,

'powers': powers,

'mde_at_80': effect_sizes[np.argmin(np.abs(np.array(powers) - 0.8))]

}

# Example: Planning an A/B test

if __name__ == "__main__":

# Scenario: Testing new checkout flow

# Baseline conversion: 3.2%

# Want to detect 0.5 percentage point increase (to 3.7%)

# That's a ~15% relative lift

result = sample_size_for_proportions(

baseline_rate=0.032,

mde_absolute=0.005, # 0.5 percentage points

alpha=0.05,

power=0.80

)

print("Sample Size Calculation")

print("=" * 40)

print(f"Baseline rate: {result['baseline_rate']:.1%}")

print(f"Target rate: {result['target_rate']:.1%}")

print(f"Relative lift: {result['mde_relative']:.1f}%")

print(f"Effect size (h): {result['effect_size_h']:.3f}")

print(f"Sample per group: {result['n_per_group']:,}")

print(f"Total sample: {result['n_total']:,}")

R

library(pwr)

sample_size_for_means <- function(

mde,

baseline_sd,

alpha = 0.05,

power = 0.80,

ratio = 1.0

) {

#' Calculate sample size for detecting difference in means

effect_size <- mde / baseline_sd

result <- pwr.t2n.test(

d = effect_size,

sig.level = alpha,

power = power,

alternative = "two.sided"

)

# For unequal allocation, use pwr.t.test with n = NULL

if (ratio == 1.0) {

result <- pwr.t.test(

d = effect_size,

sig.level = alpha,

power = power,

type = "two.sample"

)

n_per_group <- ceiling(result$n)

} else {

# Iterative solve for unequal allocation

# Simplified: use equal allocation formula with correction

result <- pwr.t.test(

d = effect_size,

sig.level = alpha,

power = power,

type = "two.sample"

)

n_control <- ceiling(result$n)

n_treatment <- ceiling(result$n * ratio)

n_per_group <- n_control

}

list(

effect_size_d = effect_size,

n_per_group = n_per_group,

n_total = n_per_group * (1 + ratio),

power = power,

alpha = alpha

)

}

sample_size_for_proportions <- function(

baseline_rate,

mde_absolute,

alpha = 0.05,

power = 0.80

) {

#' Calculate sample size for detecting difference in proportions

p1 <- baseline_rate

p2 <- baseline_rate + mde_absolute

# Cohen's h effect size for proportions

h <- 2 * asin(sqrt(p2)) - 2 * asin(sqrt(p1))

result <- pwr.2p.test(

h = h,

sig.level = alpha,

power = power

)

list(

baseline_rate = p1,

target_rate = p2,

mde_relative = (p2 - p1) / p1 * 100,

effect_size_h = h,

n_per_group = ceiling(result$n),

n_total = ceiling(result$n) * 2,

power = power,

alpha = alpha

)

}

# Precision-based planning

sample_size_for_precision <- function(

baseline_sd,

desired_ci_width,

confidence = 0.95

) {

#' Calculate sample size to achieve desired CI width

z <- qnorm(1 - (1 - confidence) / 2)

margin <- desired_ci_width / 2

# For difference of two means: SE = SD * sqrt(2/n)

# margin = z * SD * sqrt(2/n)

# n = 2 * (z * SD / margin)^2

n_per_group <- ceiling(2 * (z * baseline_sd / margin)^2)

list(

n_per_group = n_per_group,

n_total = n_per_group * 2,

expected_ci_width = desired_ci_width

)

}

# Example usage

cat("Sample Size for Proportions\n")

cat(strrep("=", 40), "\n")

result <- sample_size_for_proportions(

baseline_rate = 0.032,

mde_absolute = 0.005,

alpha = 0.05,

power = 0.80

)

cat(sprintf("Baseline rate: %.1f%%\n", result$baseline_rate * 100))

cat(sprintf("Target rate: %.1f%%\n", result$target_rate * 100))

cat(sprintf("Relative lift: %.1f%%\n", result$mde_relative))

cat(sprintf("Sample per group: %d\n", result$n_per_group))

cat(sprintf("Total sample: %d\n", result$n_total))

Precision-Based Planning Alternative

Instead of "Can I detect ?", ask "How precise will my estimate be?"

The Framework

Traditional power question: "What sample size do I need to have 80% chance of if the effect is at least d=0.2?"

Precision question: "What sample size do I need so my 95% CI for the effect is no wider than percentage points?"

Advantages of Precision Planning

- Decision-relevant: Stakeholders care about "is the effect between 5% and 15%?" not "is ?"

- Works for null results: Narrow CI around zero is informative

- Avoids dichotomous thinking: No artificial significant/not-significant boundary

- Intuitive: "We'll know the effect to within " is easier to understand than "80% power at d=0.3"

Calculation

For estimating a mean difference with 95% CI:

Example:

- SD = 25 units

- Want 95% CI within units

- per group

def sample_size_for_precision(

baseline_sd: float,

desired_ci_width: float,

confidence: float = 0.95

) -> dict:

"""

Calculate sample size to achieve desired confidence interval width.

Parameters:

-----------

baseline_sd : float

Standard deviation of the metric

desired_ci_width : float

Total CI width (e.g., for $\pm 3$, enter 6)

confidence : float

Confidence level (default 0.95)

Returns:

--------

dict with sample size and expected precision

"""

z = stats.norm.ppf(1 - (1 - confidence) / 2)

margin = desired_ci_width / 2

# For difference of two means

n_per_group = int(np.ceil(2 * (z * baseline_sd / margin) ** 2))

return {

'n_per_group': n_per_group,

'n_total': n_per_group * 2,

'expected_ci_width': desired_ci_width,

'expected_margin': margin

}

Practical Heuristics

Heuristic 1: The "10% Buffer" Rule

Always collect 10-20% more sample than your calculation suggests:

- Dropouts and invalid data happen

- Variance estimates are uncertain

- Better to have extra data than be underpowered

Heuristic 2: The "Half-Effect" Check

After calculating sample size for your MDE:

- What's your power if the true effect is half your MDE?

- If it's below 50%, you may be overconfident in your detection ability

Heuristic 3: The "Worth Running" Test

Before committing to an experiment:

- Calculate how long it takes to get required sample

- Calculate cost of running that long

- Ask: "Is the decision worth this investment if the answer could be null?"

Heuristic 4: The "Precision Reasonableness" Check

Calculate what your CI width will be with your planned sample:

- Is that precision useful for your decision?

- Can you distinguish "meaningful positive" from "meaningful negative"?

Heuristic 5: The "Worst Case" Planning

Plan for your MDE, but check:

- What's the power for effects 50% larger? (Should be >90%)

- What's the power for effects 50% smaller? (If <50%, you'll likely miss smaller real effects)

When Power Analysis Breaks Down

Case 1: Sequential Testing

Traditional power analysis assumes fixed sample size. If you're doing sequential testing (checking results as data arrives), you need different calculations that account for multiple looks.

Case 2: Multiple Comparisons

Power for detecting "at least one" effect with multiple comparisons is different from power for any single comparison. Adjust accordingly.

Case 3: Complex Designs

Clustered experiments, stratified designs, and CUPED-adjusted analyses have different power characteristics. Use simulation when formulas don't exist.

Case 4: Highly Variable Metrics

For heavy-tailed metrics (revenue, etc.), standard power calculations may be optimistic. Consider:

- Using robust methods (trimmed means)

- Transforming the metric

- Running simulations with realistic distributions

Case 5: Small True Effects

If your MDE is very small relative to variance, you may need enormous samples. Consider:

- Is this effect worth detecting?

- Can you reduce variance (CUPED, stratification)?

- Should you focus on a subset with larger expected effect?

Simulation-Based Power Analysis

When formulas don't fit, simulate:

import numpy as np

from scipy import stats

def simulate_power(

effect_size: float,

n_per_group: int,

sd: float = 1.0,

alpha: float = 0.05,

n_simulations: int = 10000,

test_func=None

) -> float:

"""

Estimate power via simulation.

Useful for complex scenarios where formulas don't exist.

"""

if test_func is None:

test_func = lambda x, y: stats.ttest_ind(x, y).pvalue

rejections = 0

for _ in range(n_simulations):

control = np.random.normal(0, sd, n_per_group)

treatment = np.random.normal(effect_size, sd, n_per_group)

p_value = test_func(control, treatment)

if p_value < alpha:

rejections += 1

return rejections / n_simulations

# Example: Power for trimmed mean comparison

from scipy.stats import trim_mean

def trimmed_mean_test(x, y, proportiontocut=0.1):

"""Bootstrap test for trimmed mean difference."""

n_boot = 1000

diffs = []

for _ in range(n_boot):

x_boot = np.random.choice(x, len(x), replace=True)

y_boot = np.random.choice(y, len(y), replace=True)

diff = trim_mean(x_boot, proportiontocut) - trim_mean(y_boot, proportiontocut)

diffs.append(diff)

# Two-sided p-value

observed_diff = trim_mean(x, proportiontocut) - trim_mean(y, proportiontocut)

p_value = 2 * min(np.mean(np.array(diffs) <= 0), np.mean(np.array(diffs) >= 0))

return p_value

# Compare power: standard t-test vs trimmed mean

# for contaminated normal (heavy tails)

def contaminated_normal(n, contamination=0.1, scale=10):

"""Generate contaminated normal data (heavy tails)."""

n_outliers = int(n * contamination)

n_normal = n - n_outliers

normal = np.random.normal(0, 1, n_normal)

outliers = np.random.normal(0, scale, n_outliers)

return np.concatenate([normal, outliers])

# This simulation shows trimmed mean has HIGHER power

# with contaminated data

Summary Table: Power Analysis Decisions

| Situation | Recommendation |

|---|---|

| Planning new experiment | Use MDE (smallest meaningful effect), not expected effect |

| Standard A/B test | Formula-based calculation is fine |

| Complex design | Use simulation |

| After null result | Report CI bounds, NOT post-hoc power |

| High-stakes decision | Power at 90%+, not just 80% |

| Exploratory analysis | 80% power acceptable |

| Expensive intervention | Consider precision planning instead |

| Sequential testing | Use group sequential methods |

| Multiple comparisons | Account for family-wise error |

Related Methods

- Effect Sizes, Confidence Intervals, and Practical Significance (Pillar) - Complete framework

- Practical Significance Thresholds - Defining MDEs

- Confidence Intervals for Non-Normal Metrics - Bootstrap methods

- Sequential Testing and Peeking - For sequential designs

Key Takeaway

Power analysis is a tool for planning, not a ritual for legitimizing sample sizes. The core question is simple: what effect would change your decision, and how confident do you need to be in detecting it? Base your MDE on business value, not statistical conventions. Don't perform post-hoc power calculations—they're mathematically meaningless. Consider precision-based planning as an alternative that focuses on estimation quality rather than significance testing. And remember: an underpowered experiment isn't just statistically weak—it's potentially a waste of resources.

References

- https://rpsychologist.com/d3/nhst/

- https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/0956797613504966

- https://statmodeling.stat.columbia.edu/2018/09/24/dont-calculate-post-hoc-power-using-observed-estimate-effect-size/

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0022103117307746

- Lakens, D. (2022). Sample size justification. *Collabra: Psychology*, 8(1), 33267.

- Gelman, A. (2018). Don't calculate post-hoc power using the observed estimate of effect size. *Statistical Modeling, Causal Inference, and Social Science* (blog).

- Simonsohn, U. (2015). Small telescopes: Detectability and the evaluation of replication results. *Psychological Science*, 26(5), 559-569.

- Maxwell, S. E., Kelley, K., & Rausch, J. R. (2008). Sample size planning for statistical power and accuracy in parameter estimation. *Annual Review of Psychology*, 59, 537-563.

Frequently Asked Questions

Why is 80% power the standard?

Should I do a post-hoc power analysis after a non-significant result?

What effect size should I use for planning?

Key Takeaway

Power analysis is a planning tool, not a ritual. Focus on the practical question: what's the smallest effect worth detecting, and how confident do you need to be in detecting it? Base sample size decisions on business value, not convention.