Contents

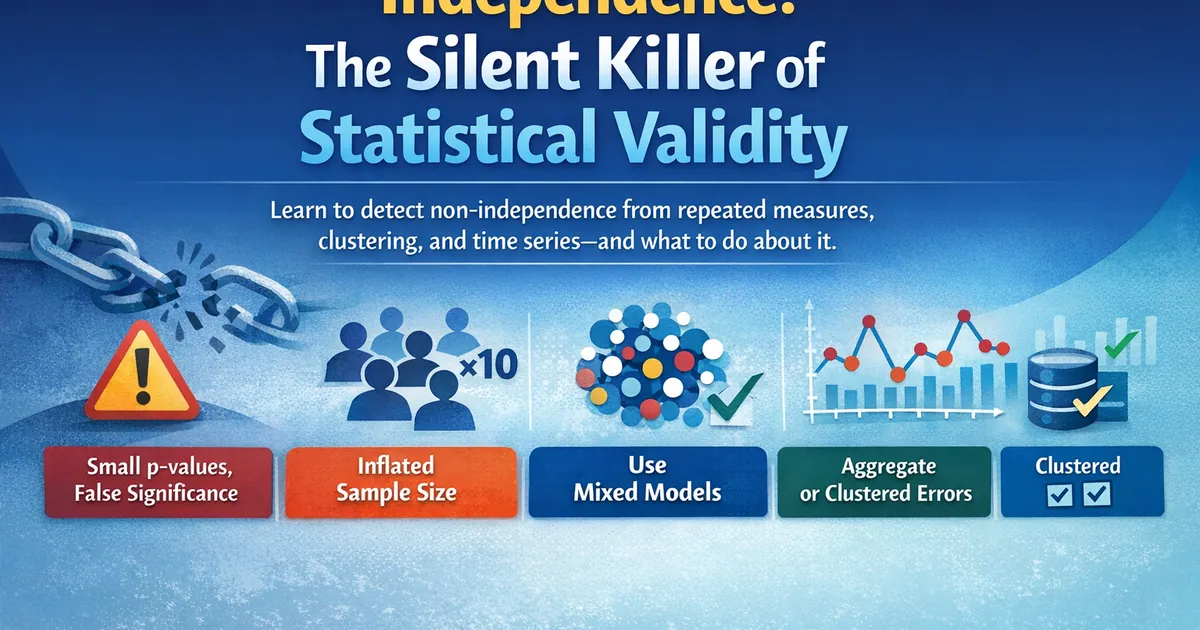

Independence: The Silent Killer of Statistical Validity

The independence assumption is the most critical and most commonly violated. Learn to detect non-independence from repeated measures, clustering, and time series—and what to do about it.

Quick Hits

- •Independence violations can't be fixed with robust methods—they require structural solutions

- •Multiple observations per user is the most common violation in product analytics

- •Ignoring clustering can inflate effective sample size by 10x or more

- •Solutions include mixed models, clustered standard errors, or aggregation

TL;DR

Independence violations are the most dangerous assumption problems because they can't be fixed with robust methods. When observations are correlated (repeated measures, clustering, time series), standard errors shrink artificially, making everything look more significant than it is. The solutions require restructuring your analysis: aggregate to independent units, use clustered standard errors, or fit models that account for the correlation structure.

What Independence Means

The Formal Definition

Observations are independent if knowing the value of one tells you nothing about another:

Practical Translation

Ask yourself: "If I know user A's value, does that help me predict user B's value?"

- Independent: Different users randomly sampled from different sources

- Not independent: Multiple purchases from the same user, students in the same classroom, time-series data

| Violation | Example | Why problematic | Effective n |

|---|---|---|---|

| Repeated measures | Multiple sessions/purchases per user | Users are consistent with themselves | Much smaller than observation count |

| Clustering | Users in same company, classroom, region | Within-cluster similarity | Closer to number of clusters than observations |

| Time series | Daily/weekly metrics | Autocorrelation — today predicts tomorrow | Depends on correlation structure |

| Network effects | Users who interact with each other | Treatment spreads through network | May need network randomization |

| Spatial correlation | Users in nearby locations | Geographic similarity | Depends on spatial structure |

The Damage: Inflated Type I Error

Simulation: How Bad Can It Get?

import numpy as np

from scipy import stats

import pandas as pd

def simulate_clustering_damage(n_sims=5000):

"""

Show how clustering inflates Type I error.

"""

np.random.seed(42)

# Scenario: 20 clusters of 10 observations each = 200 total

n_clusters = 20

cluster_size = 10

n_total = n_clusters * cluster_size

# Vary intraclass correlation (ICC)

iccs = [0, 0.1, 0.3, 0.5, 0.7]

results = {}

for icc in iccs:

# ICC determines how much variance is between vs within clusters

between_var = icc

within_var = 1 - icc

rejections_naive = 0

rejections_clustered = 0

for _ in range(n_sims):

# Generate null data (no treatment effect)

data = []

for cluster in range(n_clusters):

# Half clusters are "treatment", half are "control"

treatment = cluster >= n_clusters // 2

cluster_effect = np.random.normal(0, np.sqrt(between_var))

for _ in range(cluster_size):

obs = cluster_effect + np.random.normal(0, np.sqrt(within_var))

data.append({

'cluster': cluster,

'treatment': treatment,

'value': obs

})

df = pd.DataFrame(data)

# Naive analysis (ignores clustering)

control = df[~df['treatment']]['value']

treat = df[df['treatment']]['value']

_, p_naive = stats.ttest_ind(control, treat)

if p_naive < 0.05:

rejections_naive += 1

# Correct analysis (cluster means)

cluster_means = df.groupby(['treatment', 'cluster'])['value'].mean()

control_means = cluster_means[False].values

treat_means = cluster_means[True].values

_, p_correct = stats.ttest_ind(control_means, treat_means)

if p_correct < 0.05:

rejections_clustered += 1

results[icc] = {

'naive': rejections_naive / n_sims,

'correct': rejections_clustered / n_sims

}

print("Type I Error with Clustered Data (α = 0.05)")

print("=" * 50)

print(f"{'ICC':>6} {'Naive':>12} {'Clustered':>12} {'Inflation':>12}")

print("-" * 50)

for icc, res in results.items():

inflation = res['naive'] / 0.05

print(f"{icc:>6.1f} {res['naive']:>12.3f} {res['correct']:>12.3f} {inflation:>11.1f}x")

return results

simulate_clustering_damage()

What's Actually Happening

With clustering, your effective sample size is:

Where = total observations, = average cluster size, and = intraclass correlation.

For example, with 1,000 purchases from 100 users (m = 10 each):

| ICC | Effective n |

|---|---|

| 0.1 | 526 |

| 0.3 | 270 |

| 0.5 | 182 |

| 0.7 | 137 |

Even moderate ICC dramatically reduces the effective sample size compared to the raw 1,000 observations.

Detecting Non-Independence

Check 1: Data Structure

def check_data_structure(df, unit_col, observation_col=None):

"""

Identify potential independence violations from data structure.

"""

# Count observations per unit

obs_per_unit = df.groupby(unit_col).size()

results = {

'total_observations': len(df),

'unique_units': df[unit_col].nunique(),

'obs_per_unit': {

'mean': obs_per_unit.mean(),

'median': obs_per_unit.median(),

'max': obs_per_unit.max(),

'min': obs_per_unit.min()

},

'units_with_multiple': (obs_per_unit > 1).sum(),

'pct_from_repeat_units': (obs_per_unit[obs_per_unit > 1].sum() /

len(df) * 100 if (obs_per_unit > 1).any() else 0)

}

# Diagnosis

if results['obs_per_unit']['mean'] > 1.5:

results['warning'] = (

f"⚠️ Average of {results['obs_per_unit']['mean']:.1f} observations per unit. "

f"Independence is likely violated."

)

return results

# Example

np.random.seed(42)

n_users = 50

data = []

for user in range(n_users):

n_sessions = np.random.poisson(5) + 1

for session in range(n_sessions):

data.append({

'user_id': user,

'session_value': np.random.normal(100, 20)

})

df = pd.DataFrame(data)

structure = check_data_structure(df, 'user_id')

print("Data Structure Analysis:")

print("-" * 40)

print(f"Total observations: {structure['total_observations']}")

print(f"Unique users: {structure['unique_units']}")

print(f"Mean obs per user: {structure['obs_per_unit']['mean']:.1f}")

print(f"Max obs per user: {structure['obs_per_unit']['max']}")

if 'warning' in structure:

print(f"\n{structure['warning']}")

Check 2: Intraclass Correlation (ICC)

def calculate_icc(df, group_col, value_col):

"""

Calculate intraclass correlation coefficient.

"""

# Get group means and sizes

groups = df.groupby(group_col)[value_col]

group_means = groups.mean()

group_sizes = groups.size()

grand_mean = df[value_col].mean()

n_groups = len(group_means)

n_total = len(df)

avg_size = n_total / n_groups

# Between-group variance

ss_between = sum(group_sizes * (group_means - grand_mean)**2)

ms_between = ss_between / (n_groups - 1)

# Within-group variance

ss_within = sum(groups.apply(lambda x: sum((x - x.mean())**2)))

ms_within = ss_within / (n_total - n_groups)

# ICC (one-way random effects)

icc = (ms_between - ms_within) / (ms_between + (avg_size - 1) * ms_within)

icc = max(0, icc) # Can't be negative

# Effective sample size

n_eff = n_total / (1 + (avg_size - 1) * icc)

return {

'icc': icc,

'n_total': n_total,

'n_groups': n_groups,

'avg_group_size': avg_size,

'effective_n': n_eff,

'design_effect': 1 + (avg_size - 1) * icc

}

# Calculate ICC for our example

icc_result = calculate_icc(df, 'user_id', 'session_value')

print("Intraclass Correlation Analysis:")

print("-" * 40)

print(f"ICC: {icc_result['icc']:.3f}")

print(f"Total observations: {icc_result['n_total']}")

print(f"Effective sample size: {icc_result['effective_n']:.0f}")

print(f"Design effect: {icc_result['design_effect']:.1f}")

Check 3: Autocorrelation (Time Series)

from scipy.stats import pearsonr

def check_autocorrelation(series, max_lag=5):

"""

Check for autocorrelation in time series data.

"""

series = np.array(series)

n = len(series)

results = {'lags': []}

for lag in range(1, min(max_lag + 1, n // 4)):

corr, p = pearsonr(series[:-lag], series[lag:])

results['lags'].append({

'lag': lag,

'correlation': corr,

'p_value': p

})

# Durbin-Watson statistic

residuals = series - np.mean(series)

dw = np.sum(np.diff(residuals)**2) / np.sum(residuals**2)

results['durbin_watson'] = dw

# DW ≈ 2 means no autocorrelation

# DW < 2 means positive autocorrelation

# DW > 2 means negative autocorrelation

return results

# Example: Daily metrics

np.random.seed(42)

daily_metric = np.cumsum(np.random.normal(0.1, 1, 100)) + 100 # Random walk

auto_result = check_autocorrelation(daily_metric)

print("Autocorrelation Check:")

print("-" * 40)

print(f"Durbin-Watson: {auto_result['durbin_watson']:.2f} (2 = no autocorrelation)")

print("\nLag correlations:")

for lag_info in auto_result['lags'][:3]:

print(f" Lag {lag_info['lag']}: r = {lag_info['correlation']:.3f}, "

f"p = {lag_info['p_value']:.4f}")

Solutions

Solution 1: Aggregate to Independent Units

The simplest solution: collapse data to one observation per independent unit.

def aggregate_solution(df, unit_col, value_col, group_col=None):

"""

Aggregate to unit level to restore independence.

"""

if group_col:

# Aggregate within groups

aggregated = df.groupby([group_col, unit_col]).agg({

value_col: ['mean', 'std', 'count']

}).reset_index()

aggregated.columns = [group_col, unit_col, 'mean', 'std', 'n_obs']

else:

aggregated = df.groupby(unit_col).agg({

value_col: ['mean', 'std', 'count']

}).reset_index()

aggregated.columns = [unit_col, 'mean', 'std', 'n_obs']

return aggregated

# Example: Compare treatment vs control

np.random.seed(42)

data = []

for user in range(100):

treatment = user >= 50

user_effect = np.random.normal(0, 5)

treatment_effect = 3 if treatment else 0

for session in range(np.random.poisson(5) + 1):

data.append({

'user_id': user,

'treatment': treatment,

'value': 50 + user_effect + treatment_effect + np.random.normal(0, 10)

})

df = pd.DataFrame(data)

# Wrong: observation-level analysis

control_obs = df[~df['treatment']]['value']

treat_obs = df[df['treatment']]['value']

_, p_wrong = stats.ttest_ind(control_obs, treat_obs)

# Right: user-level analysis

user_means = df.groupby(['treatment', 'user_id'])['value'].mean().reset_index()

control_users = user_means[~user_means['treatment']]['value']

treat_users = user_means[user_means['treatment']]['value']

_, p_right = stats.ttest_ind(control_users, treat_users)

print("Impact of Aggregation:")

print("-" * 40)

print(f"Observation-level (WRONG): n = {len(df)}, p = {p_wrong:.4f}")

print(f"User-level (RIGHT): n = {len(user_means)}, p = {p_right:.4f}")

Solution 2: Clustered Standard Errors

For regression, adjust standard errors to account for clustering.

import statsmodels.api as sm

def clustered_regression(df, outcome_col, predictor_cols, cluster_col):

"""

Regression with clustered standard errors.

"""

y = df[outcome_col]

X = sm.add_constant(df[predictor_cols])

# Standard OLS

model_standard = sm.OLS(y, X).fit()

# With clustered standard errors

model_clustered = sm.OLS(y, X).fit(cov_type='cluster',

cov_kwds={'groups': df[cluster_col]})

return model_standard, model_clustered

# Example

np.random.seed(42)

# Create clustered data with treatment effect

data = []

for cluster in range(50):

treatment = cluster >= 25

cluster_effect = np.random.normal(0, 10)

for _ in range(np.random.poisson(10) + 1):

value = 50 + cluster_effect + (5 if treatment else 0) + np.random.normal(0, 5)

data.append({

'cluster': cluster,

'treatment': int(treatment),

'value': value

})

df = pd.DataFrame(data)

model_std, model_clust = clustered_regression(df, 'value', ['treatment'], 'cluster')

print("Regression Results Comparison:")

print("-" * 50)

print(f"{'':20} {'Standard SE':>15} {'Clustered SE':>15}")

print("-" * 50)

for var in ['const', 'treatment']:

se_std = model_std.bse[var]

se_clust = model_clust.bse[var]

ratio = se_clust / se_std

print(f"{var:20} {se_std:>15.3f} {se_clust:>15.3f} ({ratio:.1f}x)")

print("\nP-values for treatment:")

print(f" Standard: {model_std.pvalues['treatment']:.4f}")

print(f" Clustered: {model_clust.pvalues['treatment']:.4f}")

Solution 3: Mixed Effects Models

For complex structures, use multilevel/mixed models.

import statsmodels.formula.api as smf

def mixed_model_analysis(df, outcome, fixed_effects, random_effects):

"""

Fit mixed effects model.

"""

formula = f"{outcome} ~ {fixed_effects}"

model = smf.mixedlm(formula, df, groups=random_effects).fit()

return model

# Example: Users nested in companies

np.random.seed(42)

data = []

for company in range(20):

company_effect = np.random.normal(0, 10)

treatment = company >= 10

for user in range(np.random.randint(5, 15)):

user_effect = np.random.normal(0, 5)

for session in range(np.random.poisson(3) + 1):

value = (50 + company_effect + user_effect +

(5 if treatment else 0) + np.random.normal(0, 3))

data.append({

'company': company,

'user': f"{company}_{user}",

'treatment': int(treatment),

'value': value

})

df = pd.DataFrame(data)

# Fit mixed model (random intercept for company)

model = smf.mixedlm("value ~ treatment", df, groups="company").fit()

print("Mixed Model Results:")

print("-" * 50)

print(model.summary().tables[1])

Decision Framework

Do observations repeat within units (users, clusters, time)?

│

├── NO → Standard methods OK

│

└── YES → How to handle?

│

├── Simple structure (one observation per unit possible)?

│ └── Aggregate to unit means

│

├── Need observation-level analysis?

│ ├── Regression → Clustered standard errors

│ └── Complex nesting → Mixed effects models

│

└── Time series?

└── Time series methods (ARIMA, etc.)

R Implementation

# Check for clustering

check_clustering <- function(df, unit_col, value_col) {

library(ICC)

# ICC calculation

icc_result <- ICCbare(unit_col, value_col, data = df)

# Effective sample size

n_total <- nrow(df)

n_units <- length(unique(df[[unit_col]]))

avg_size <- n_total / n_units

n_eff <- n_total / (1 + (avg_size - 1) * icc_result)

cat("Independence Check\n")

cat(rep("=", 40), "\n")

cat(sprintf("Total observations: %d\n", n_total))

cat(sprintf("Unique units: %d\n", n_units))

cat(sprintf("ICC: %.3f\n", icc_result))

cat(sprintf("Effective n: %.0f\n", n_eff))

}

# Clustered standard errors

library(sandwich)

library(lmtest)

model <- lm(value ~ treatment, data = df)

coeftest(model, vcov = vcovCL(model, cluster = df$cluster))

# Mixed effects model

library(lme4)

model <- lmer(value ~ treatment + (1|cluster), data = df)

summary(model)

Related Methods

- Assumption Checks Master Guide — The pillar article

- Clustered Experiments — A/B tests with clustering

- Paired vs. Independent Data — When data is paired

Key Takeaway

Independence is the most critical assumption because violations cannot be fixed with robust methods. When observations are clustered (repeated measures, grouped data, time series), your effective sample size is smaller than your observation count—sometimes dramatically so. The solutions require structural changes: aggregate to independent units, use clustered standard errors, or fit mixed models. Always ask: "Are my observations truly independent?"

References

- https://www.jstor.org/stable/2531734

- https://doi.org/10.1037/a0014694

- Aarts, E., Verhage, M., Veenvliet, J. V., Dolan, C. V., & Van Der Sluis, S. (2014). A solution to dependency: using multilevel analysis to accommodate nested data. *Nature Neuroscience*, 17(4), 491-496.

- Moulton, B. R. (1986). Random group effects and the precision of regression estimates. *Journal of Econometrics*, 32(3), 385-397.

- Snijders, T. A., & Bosker, R. J. (2011). *Multilevel Analysis: An Introduction to Basic and Advanced Multilevel Modeling* (2nd ed.). Sage.

Frequently Asked Questions

What happens if I ignore non-independence?

Can I just use a robust test to fix this?

How do I know if my data is independent?

Key Takeaway

Independence is the most important and most commonly violated assumption. Unlike normality or equal variance, violations cannot be fixed by using robust methods—they require fundamentally different approaches: aggregating to independent units, using clustered standard errors, or fitting mixed/multilevel models.