Contents

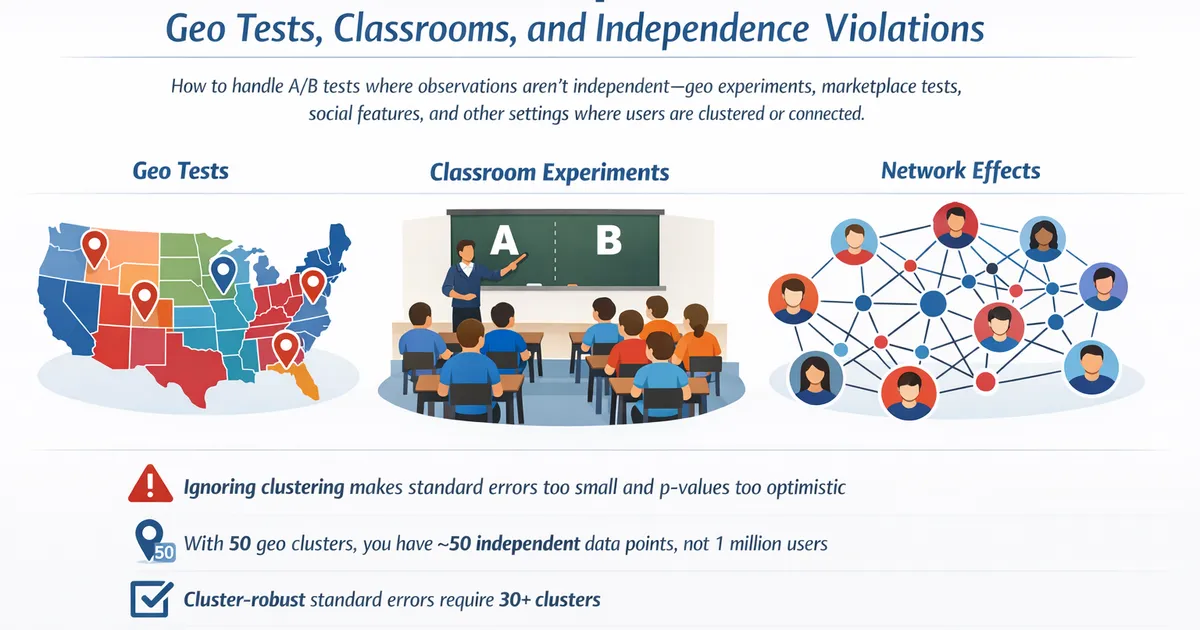

Clustered Experiments: Geo Tests, Classrooms, and Independence Violations

How to handle A/B tests where observations aren't independent—geo experiments, marketplace tests, social features, and other settings where users are clustered or connected.

Quick Hits

- •Ignoring clustering makes standard errors too small and p-values too optimistic

- •With 50 geo clusters, you have ~50 independent data points, not 1 million users

- •Cluster-robust standard errors are simple to implement but need 30+ clusters

- •Network effects (social, marketplace) are the hardest—randomization itself may be compromised

TL;DR

Standard A/B testing assumes independent observations: User A's outcome doesn't affect User B's. This assumption fails in geo experiments, marketplace tests, social features, and many other settings. When observations are clustered or connected, your effective sample size is much smaller than your user count, and ignoring this leads to false positives. Use cluster-robust methods to get valid inference.

Why Independence Matters

The Independence Assumption

Classical hypothesis tests assume observations are independent and identically distributed (IID). This means:

- User A's outcome is statistically unrelated to User B's

- Both are drawn from the same underlying distribution

When true, variance of the sample mean is:

With 100,000 users, you have 100,000 independent data points.

What Happens When Independence Fails

If observations are correlated within clusters, variance is larger than the IID formula predicts:

Where:

- = average cluster size

- = intra-cluster correlation (ICC)

This factor is the design effect or variance inflation factor.

import numpy as np

def design_effect(cluster_size, icc):

"""Calculate variance inflation due to clustering."""

return 1 + (cluster_size - 1) * icc

# Example: 50 geo clusters, 2000 users each, ICC = 0.01

n_users = 50 * 2000 # 100,000

cluster_size = 2000

icc = 0.01

deff = design_effect(cluster_size, icc)

effective_n = n_users / deff

print(f"Nominal n: {n_users:,}")

print(f"Design effect: {deff:.1f}")

print(f"Effective n: {effective_n:,.0f}")

# Output: Effective n: ~4,975 (not 100,000!)

Even with a tiny ICC of 0.01, effective sample size drops 20-fold.

Common Clustering Scenarios

Geo Experiments

Structure: Treatment assigned at region level (cities, DMAs, countries). All users in a region share treatment.

Why correlated: Users in same region share local events, weather, competitors, advertising exposure.

Cluster count: Often 10-100 regions, far fewer than user count.

Marketplace Experiments

Structure: Testing seller-side changes affects buyer experience, and vice versa.

Why correlated: Buyers compete for listings; sellers compete for buyers. One user's action affects others' outcomes.

Complication: Network structure means clustering isn't clean—everyone affects everyone.

Social Feature Experiments

Structure: Testing sharing, referrals, or viral features.

Why correlated: User A's sharing affects User B's engagement. Treatment "leaks" across users.

Complication: Treatment assignment itself is compromised (control users exposed via treated friends).

Classroom/Team Experiments

Structure: Intervention applied to classrooms, teams, or organizations.

Why correlated: Students in same class share teacher, curriculum, peer effects.

Cluster count: Often limited (10-50 classes).

Device/Household Clustering

Structure: Same user on multiple devices, or multiple users sharing account/household.

Why correlated: Observations from same person/household aren't independent.

Often ignored: Many teams don't even recognize this clustering exists.

Method 1: Cluster-Robust Standard Errors

The simplest fix: use standard errors that account for arbitrary correlation within clusters.

Python Implementation

import statsmodels.api as sm

import pandas as pd

import numpy as np

def cluster_robust_ttest(data, outcome_col, treatment_col, cluster_col):

"""

Regression-based test with cluster-robust standard errors.

"""

# Add constant for intercept

X = sm.add_constant(data[treatment_col])

y = data[outcome_col]

# Fit OLS

model = sm.OLS(y, X)

# Cluster-robust standard errors

results = model.fit(cov_type='cluster', cov_kwds={'groups': data[cluster_col]})

# Extract treatment effect

coef = results.params[treatment_col]

se = results.bse[treatment_col]

ci_lower, ci_upper = results.conf_int().loc[treatment_col]

p_value = results.pvalues[treatment_col]

return {

'effect': coef,

'se_clustered': se,

'ci': (ci_lower, ci_upper),

'p_value': p_value,

'n_clusters': data[cluster_col].nunique()

}

# Example

np.random.seed(42)

n_clusters = 50

users_per_cluster = 2000

# Generate clustered data

data = []

for i in range(n_clusters):

treatment = i % 2 # Alternating assignment

cluster_effect = np.random.normal(0, 1) # Shared within cluster

for j in range(users_per_cluster):

outcome = treatment * 0.1 + cluster_effect + np.random.normal(0, 1)

data.append({

'cluster': i,

'treatment': treatment,

'outcome': outcome

})

df = pd.DataFrame(data)

# Compare naive vs clustered SE

naive_result = sm.OLS(df['outcome'], sm.add_constant(df['treatment'])).fit()

clustered_result = cluster_robust_ttest(df, 'outcome', 'treatment', 'cluster')

print("Naive analysis (ignoring clustering):")

print(f" SE: {naive_result.bse['treatment']:.4f}")

print(f" p-value: {naive_result.pvalues['treatment']:.4f}")

print("\nCluster-robust analysis:")

print(f" SE: {clustered_result['se_clustered']:.4f}")

print(f" p-value: {clustered_result['p_value']:.4f}")

print(f" N clusters: {clustered_result['n_clusters']}")

R Implementation

library(sandwich)

library(lmtest)

# Fit model

model <- lm(outcome ~ treatment, data = df)

# Cluster-robust standard errors

coeftest(model, vcov = vcovCL(model, cluster = df$cluster))

Requirements

- 30+ clusters: Cluster-robust SEs rely on asymptotics in the number of clusters

- Balanced clusters: Very unequal cluster sizes can cause issues

- Treatment varies within and between clusters: If treatment is constant within clusters (geo experiments), you're comparing cluster means

Method 2: Cluster-Level Analysis

The simplest approach: aggregate to cluster means and analyze clusters as the unit.

Implementation

def cluster_level_analysis(data, outcome_col, treatment_col, cluster_col):

"""

Aggregate to cluster level and run t-test.

"""

# Aggregate to cluster means

cluster_data = data.groupby(cluster_col).agg({

outcome_col: 'mean',

treatment_col: 'first' # Same within cluster

}).reset_index()

# T-test on cluster means

control = cluster_data[cluster_data[treatment_col] == 0][outcome_col]

treatment = cluster_data[cluster_data[treatment_col] == 1][outcome_col]

from scipy import stats

t_stat, p_value = stats.ttest_ind(control, treatment, equal_var=False)

return {

'control_mean': control.mean(),

'treatment_mean': treatment.mean(),

'effect': treatment.mean() - control.mean(),

'p_value': p_value,

'n_clusters_control': len(control),

'n_clusters_treatment': len(treatment)

}

result = cluster_level_analysis(df, 'outcome', 'treatment', 'cluster')

print(f"Effect: {result['effect']:.4f}")

print(f"P-value: {result['p_value']:.4f}")

print(f"N clusters: {result['n_clusters_control']} control, {result['n_clusters_treatment']} treatment")

Pros and Cons

Pros:

- Simple and transparent

- Valid with few clusters

- Easy to explain

Cons:

- Loses information about within-cluster variation

- All clusters weighted equally (ignores size differences)

- Less power than cluster-robust regression

Method 3: Mixed/Hierarchical Models

Model the clustering structure explicitly, allowing both cluster-level and individual-level variation.

Python Implementation

import statsmodels.formula.api as smf

def mixed_model_analysis(data, outcome_col, treatment_col, cluster_col):

"""

Mixed effects model with random cluster intercepts.

"""

formula = f"{outcome_col} ~ {treatment_col}"

model = smf.mixedlm(formula, data, groups=data[cluster_col])

result = model.fit()

return {

'effect': result.params[treatment_col],

'se': result.bse[treatment_col],

'p_value': result.pvalues[treatment_col],

'cluster_variance': result.cov_re.iloc[0, 0],

'residual_variance': result.scale

}

result = mixed_model_analysis(df, 'outcome', 'treatment', 'cluster')

print(f"Effect: {result['effect']:.4f}")

print(f"P-value: {result['p_value']:.4f}")

print(f"Cluster variance: {result['cluster_variance']:.4f}")

R Implementation

library(lme4)

library(lmerTest)

model <- lmer(outcome ~ treatment + (1|cluster), data = df)

summary(model)

When to Use

- Moderate number of clusters (10-100)

- Want to estimate variance components

- Have covariates at different levels

Method 4: Randomization Inference

When cluster count is very small (< 15), asymptotic methods break down. Randomization inference computes exact p-values.

The Idea

Under the sharp null (no effect for any unit), we know what every potential outcome would be. Compute the test statistic for all possible random assignments.

Implementation

from itertools import combinations

from scipy import stats

def randomization_inference(data, outcome_col, treatment_col, cluster_col):

"""

Randomization inference for cluster-randomized experiments.

"""

# Get cluster-level data

cluster_data = data.groupby(cluster_col).agg({

outcome_col: 'mean',

treatment_col: 'first'

}).reset_index()

clusters = cluster_data[cluster_col].values

outcomes = cluster_data[outcome_col].values

treatment = cluster_data[treatment_col].values

n_treated = treatment.sum()

n_clusters = len(clusters)

# Observed test statistic

treated_mean = outcomes[treatment == 1].mean()

control_mean = outcomes[treatment == 0].mean()

observed_diff = treated_mean - control_mean

# Enumerate all possible assignments (or sample if too many)

all_diffs = []

for treated_idx in combinations(range(n_clusters), int(n_treated)):

t_mean = outcomes[list(treated_idx)].mean()

c_idx = [i for i in range(n_clusters) if i not in treated_idx]

c_mean = outcomes[c_idx].mean()

all_diffs.append(t_mean - c_mean)

# P-value: proportion of assignments as extreme as observed

all_diffs = np.array(all_diffs)

p_value = np.mean(np.abs(all_diffs) >= np.abs(observed_diff))

return {

'observed_diff': observed_diff,

'p_value': p_value,

'n_permutations': len(all_diffs)

}

# With few clusters (warning: combinatorially explosive for many clusters)

# This example assumes small cluster count

Requirements

- Few clusters: Enumeration is feasible for ~10-15 clusters

- For more clusters: Use Monte Carlo sampling of permutations

Network Interference

When treatment of one unit affects outcomes of other units (social features, marketplace), all methods above struggle.

Detecting Interference

Look for signs that treatment "leaks":

- Control users connected to treated users have different outcomes

- Treatment effect varies by network position

- Aggregate metrics (market-level) show effects when individual metrics don't

Approaches

Cluster by network: Randomize at community/cluster level to contain interference.

Ego-cluster randomization: Randomize focal users and include their network in analysis.

Exposure modeling: Estimate "dose" of treatment each control user receives.

def estimate_network_exposure(user_id, treatment_status, network_edges):

"""

Calculate what fraction of a user's connections are treated.

"""

connections = [edge[1] for edge in network_edges if edge[0] == user_id]

if not connections:

return 0

treated_connections = sum(treatment_status.get(c, 0) for c in connections)

return treated_connections / len(connections)

This is a complex topic deserving its own treatment—the key point is recognizing when standard methods fail.

Practical Checklist

Before analyzing clustered data:

- Identify clustering: What makes observations correlated?

- Count clusters: How many independent units do you really have?

- Estimate ICC: What fraction of variance is between-cluster?

- Choose method: Cluster-robust SE (30+ clusters), cluster-level analysis (few clusters), or mixed models

- Check balance: Are clusters balanced on pre-experiment characteristics?

- Consider network effects: Does treatment of A affect B's outcome?

Related Methods

- A/B Testing Statistical Methods for Product Teams — Complete guide to A/B testing

- Independence: The Silent Killer — More on independence violations

- Robust Standard Errors: When to Use by Default — Broader SE correction context

Frequently Asked Questions

Q: My geo experiment has only 10 DMAs. What can I do? A: Use cluster-level analysis (t-test on DMA means) or randomization inference. Don't use cluster-robust SEs with so few clusters.

Q: How do I estimate ICC? A: Fit a random intercept model and compute . Or use ANOVA: .

Q: Should I always use cluster-robust standard errors? A: If there's any reasonable clustering structure, yes. The cost of unnecessary correction is small (slightly wider CIs). The cost of missing needed correction is high (invalid inference).

Q: What about time-series dependence (same user over time)? A: Cluster by user. Each user's observations are correlated; different users are independent.

Key Takeaway

The independence assumption is the quiet killer of A/B test validity. When observations are clustered—by geography, network, or shared environment—standard errors shrink and false positives inflate. Always ask: "What is my unit of randomization, and how many independent units do I have?" For geo experiments with 50 regions, you have ~50 data points, not millions of users. Plan accordingly.

References

- https://www.jstor.org/stable/2171844

- https://arxiv.org/abs/2106.07263

- Cameron, A. C., Gelbach, J. B., & Miller, D. L. (2008). Bootstrap-based improvements for inference with clustered errors. *The Review of Economics and Statistics*, 90(3), 414-427.

- Abadie, A., Athey, S., Imbens, G. W., & Wooldridge, J. M. (2023). When should you adjust standard errors for clustering? *The Quarterly Journal of Economics*, 138(1), 1-35.

- Eckles, D., Karrer, B., & Ugander, J. (2017). Design and analysis of experiments in networks: Reducing bias from interference. *Journal of Causal Inference*, 5(1).

Frequently Asked Questions

How many clusters do I need for reliable inference?

Can I just aggregate to cluster means and run a t-test?

What about users who appear in multiple clusters (e.g., travel across geos)?

Key Takeaway

The independence assumption is the quiet killer of A/B test validity. When observations are clustered—by geography, network, or shared environment—standard errors shrink and false positives inflate. Always ask: 'What is my unit of randomization, and how many independent units do I have?'