Contents

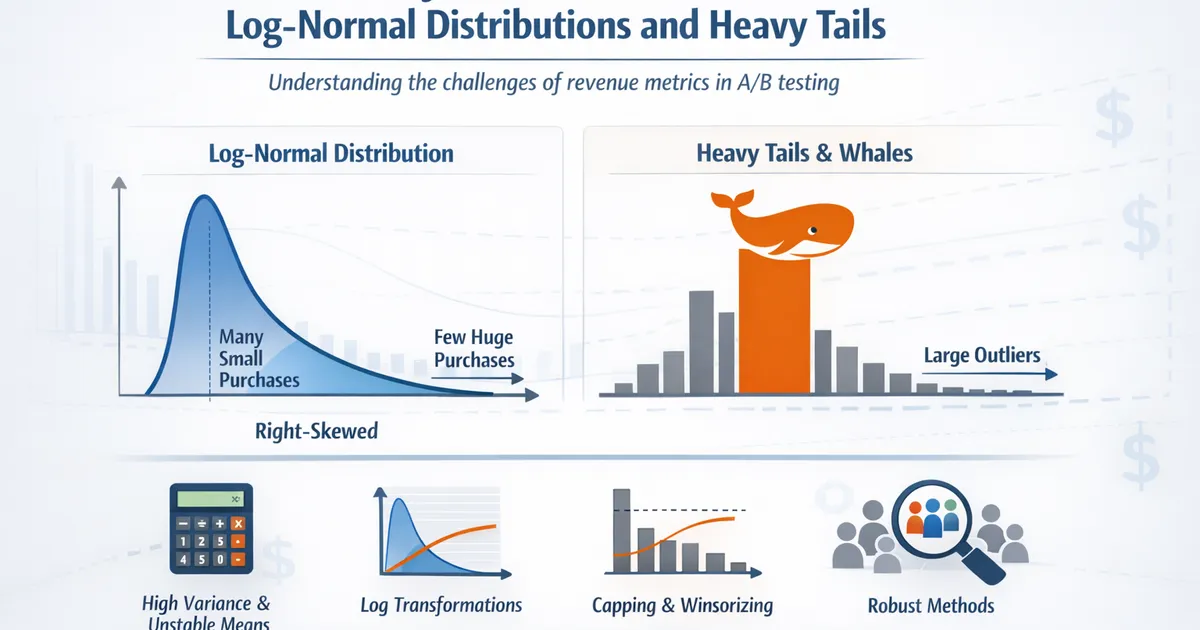

Why Revenue Is Hard: Log-Normal Distributions and Heavy Tails

A deep dive into why revenue metrics are statistically challenging. Learn about log-normal distributions, heavy tails, whale effects, and practical approaches to analyzing revenue in A/B tests.

Quick Hits

- •Revenue is typically right-skewed: many small values, few very large ones

- •A single whale can shift your experiment's mean by more than the treatment effect

- •Standard errors on revenue metrics are huge - you need massive samples

- •Log transformation helps but changes the question (geometric vs. arithmetic mean)

- •Capping/Winsorizing is common but requires disclosure and sensitivity analysis

TL;DR

Revenue data is statistically difficult because it combines three challenges: many zeros (non-purchasers), right-skew (most purchases are small), and heavy tails (occasional large purchases). A single "whale" customer can shift your experiment's mean by more than your treatment effect. Standard t-tests have poor power and unstable results. Solutions include log transformation (changes interpretation), capping/Winsorization (reduces extreme influence), and CUPED (reduces variance).

The Three Challenges of Revenue

Challenge 1: Many Zeros

In most products, the majority of users don't purchase:

- E-commerce: 2-5% conversion rate → 95-98% zeros

- SaaS with free tier: 5-15% paid → 85-95% zeros

- Games: 1-5% paying players → 95-99% zeros

Problem: Can't log-transform zeros. Two distinct populations (purchasers vs. non-purchasers).

Challenge 2: Right Skew

Among purchasers, most buy small amounts:

- Many $10-50 purchases

- Some $100-500 purchases

- Few $1000+ purchases

Problem: Mean is much higher than median. "Average" doesn't represent typical behavior.

Challenge 3: Heavy Tails

The top 1% of customers often generate 50%+ of revenue:

- Whales: Individual customers spending the median

- Not outliers—they're part of your business model

Problem: A few extreme values dominate sample statistics.

The Whale Problem

One Customer, Big Impact

Example:

- Control: 10,000 users, mean revenue = $5.00

- Treatment: 10,000 users, mean revenue = $5.30

Looks like a 6% lift! But...

One treatment user spent $3,500 (a whale). Remove that whale: Treatment mean = $4.95

The whale contributed half the observed effect.

Why This Matters

| Scenario | Conclusion |

|---|---|

| Whale in treatment | False positive (inflated effect) |

| Whale in control | False negative (hidden real effect) |

| Random | High variance, low power |

Whale assignment is random, but their impact is huge.

Math: Why Heavy Tails = Huge Variance

For a log-normal distribution with mean and variance on the log scale:

Variance grows exponentially with . With typical revenue parameters, variance can be the squared mean.

What "Heavy Tails" Actually Means

Tail Behavior

Normal distribution: 99.7% of values within 3 standard deviations

Heavy-tailed: Extreme values occur much more often than normal predicts

Example:

| Metric | Normal (SD=10) | Log-Normal () |

|---|---|---|

| P(X > 30) | 0.1% | 5% |

| P(X > 50) | ~0% | 1% |

| P(X > 100) | ~0% | 0.1% |

Impact on Statistics

| Property | Normal | Heavy-Tailed |

|---|---|---|

| CLT convergence | Fast (~30 samples) | Slow (100s-1000s) |

| Mean stability | Good | Poor |

| Outlier influence | Limited | Dominant |

| Required sample size | Moderate | Large |

Code: Simulating the Problem

import numpy as np

import pandas as pd

from scipy import stats

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

def simulate_revenue_experiment(n_per_group=5000, true_lift=0.05, n_simulations=1000):

"""

Simulate revenue A/B tests to show the whale problem.

"""

results = []

for sim in range(n_simulations):

# Generate control revenue

# 70% zeros, 30% log-normal purchases

is_purchaser_c = np.random.binomial(1, 0.3, n_per_group)

revenue_c = np.where(

is_purchaser_c,

np.random.lognormal(mean=2.5, sigma=1.5, size=n_per_group),

0

)

# Treatment: slightly higher mean log revenue

is_purchaser_t = np.random.binomial(1, 0.3, n_per_group)

revenue_t = np.where(

is_purchaser_t,

np.random.lognormal(mean=2.5 + np.log(1 + true_lift), sigma=1.5, size=n_per_group),

0

)

# Standard t-test

t_stat, p_value = stats.ttest_ind(revenue_c, revenue_t)

# Effect estimate

mean_c = np.mean(revenue_c)

mean_t = np.mean(revenue_t)

observed_lift = (mean_t - mean_c) / mean_c if mean_c > 0 else 0

# Check for whale influence

max_c = np.max(revenue_c)

max_t = np.max(revenue_t)

whale_influence = max(max_c, max_t) / (n_per_group * max(mean_c, mean_t))

results.append({

'mean_control': mean_c,

'mean_treatment': mean_t,

'observed_lift': observed_lift,

'p_value': p_value,

'significant': p_value < 0.05,

'max_control': max_c,

'max_treatment': max_t,

'whale_influence': whale_influence

})

return pd.DataFrame(results)

def analyze_simulation_results(results, true_lift):

"""

Analyze simulation results.

"""

print("Revenue A/B Test Simulation Results")

print("=" * 50)

print(f"True lift: {true_lift:.1%}")

print(f"\nObserved lift distribution:")

print(f" Mean: {results['observed_lift'].mean():.1%}")

print(f" Median: {results['observed_lift'].median():.1%}")

print(f" Std Dev: {results['observed_lift'].std():.1%}")

print(f" Min: {results['observed_lift'].min():.1%}")

print(f" Max: {results['observed_lift'].max():.1%}")

print(f"\nPower (correctly detect true effect):")

print(f" Significant and lift > 0: {(results['significant'] & (results['observed_lift'] > 0)).mean():.1%}")

print(f"\nEffect of whales:")

high_whale = results['whale_influence'] > results['whale_influence'].median()

print(f" High whale experiments - Lift std: {results.loc[high_whale, 'observed_lift'].std():.1%}")

print(f" Low whale experiments - Lift std: {results.loc[~high_whale, 'observed_lift'].std():.1%}")

# Run simulation

np.random.seed(42)

results = simulate_revenue_experiment(n_per_group=5000, true_lift=0.05, n_simulations=1000)

analyze_simulation_results(results, 0.05)

# Plot distribution of observed effects

fig, axes = plt.subplots(1, 2, figsize=(12, 4))

axes[0].hist(results['observed_lift'], bins=50, edgecolor='white')

axes[0].axvline(0.05, color='red', linestyle='--', label='True lift')

axes[0].axvline(results['observed_lift'].mean(), color='blue', linestyle='--', label='Mean observed')

axes[0].set_xlabel('Observed Lift')

axes[0].set_ylabel('Count')

axes[0].set_title('Distribution of Observed Lift')

axes[0].legend()

axes[1].scatter(results['max_treatment'], results['observed_lift'], alpha=0.3)

axes[1].axhline(0.05, color='red', linestyle='--')

axes[1].set_xlabel('Max Treatment Revenue (Whale Size)')

axes[1].set_ylabel('Observed Lift')

axes[1].set_title('Whale Impact on Observed Lift')

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

Solutions

Solution 1: Log Transformation

Transform to log scale, where data is more normal.

# Log-transform non-zero values

revenue_log = np.log(revenue[revenue > 0])

# Run t-test on log values

t_stat, p_value = stats.ttest_ind(log_control, log_treatment)

# Effect is ratio (geometric mean)

log_diff = np.mean(log_treatment) - np.mean(log_control)

ratio = np.exp(log_diff) # e.g., 1.05 = 5% higher geometric mean

Pros: Well-behaved statistics Cons: Ignores zeros, measures geometric mean (not total revenue)

Solution 2: Winsorization/Capping

Cap extreme values at a percentile.

def winsorize(x, lower=0.01, upper=0.99):

"""Cap values at percentiles."""

lower_bound = np.percentile(x, lower * 100)

upper_bound = np.percentile(x, upper * 100)

return np.clip(x, lower_bound, upper_bound)

revenue_capped = winsorize(revenue, lower=0, upper=0.99)

Pros: Reduces whale influence, keeps all users Cons: Somewhat arbitrary cutoff, requires disclosure

Solution 3: CUPED (Variance Reduction)

Use pre-experiment data to reduce variance.

# Pre-experiment revenue

pre_revenue = data['pre_experiment_revenue']

post_revenue = data['experiment_revenue']

# CUPED adjustment

theta = np.cov(post_revenue, pre_revenue)[0, 1] / np.var(pre_revenue)

adjusted_revenue = post_revenue - theta * (pre_revenue - np.mean(pre_revenue))

Pros: Can reduce variance 20-50%, preserves mean interpretation Cons: Requires pre-experiment data

Solution 4: Trimmed Means

Remove top/bottom X% before computing mean.

from scipy.stats import trim_mean

# 5% trimmed mean (removes top and bottom 5%)

trimmed_control = trim_mean(revenue_control, 0.05)

trimmed_treatment = trim_mean(revenue_treatment, 0.05)

Pros: Robust to extremes Cons: Changes what you're measuring

Solution 5: Quantile Analysis

Report effects at different percentiles.

for pct in [50, 75, 90, 95]:

q_c = np.percentile(revenue_control, pct)

q_t = np.percentile(revenue_treatment, pct)

print(f"P{pct}: Control={q_c:.2f}, Treatment={q_t:.2f}")

Pros: Rich picture of distribution shift Cons: More complex to interpret

Comparison of Methods

| Method | Handles Zeros | Robust to Whales | Estimates Total Revenue | Interpretable |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standard t-test | Yes | No | Yes | Yes |

| Log transformation | No | Yes | No (geometric mean) | Moderate |

| Winsorization | Yes | Yes | Approx | Yes |

| CUPED | Yes | Partial | Yes | Yes |

| Trimmed mean | Yes | Yes | No (subset) | Moderate |

| Bootstrap | Yes | Partial | Yes | Yes |

Reporting Guidelines

When Using Modified Methods

Always disclose:

- What modification you used (capping at 99th percentile, 10% trim, etc.)

- Why (high variance due to heavy tails)

- Sensitivity analysis (results with and without modification)

Example:

"Revenue was capped at the 99th percentile ($500) to reduce whale-driven variance. With capping: +5.2% lift (95% CI: 2.1% to 8.3%, ) Without capping: +4.8% lift (95% CI: -3.2% to 12.8%, )"

Sample Size Implications

Expect to need the sample size for revenue vs. conversion rates.

| Metric | Typical MDE | Typical n per group |

|---|---|---|

| Conversion rate | 5% relative | 10,000-50,000 |

| Revenue per user | 5% relative | 50,000-500,000 |

Related Methods

- Metric Distributions (Pillar) - Full distributions overview

- Winsorization and Trimming - Outlier handling details

- Bootstrap for Heavy-Tailed Metrics - Non-parametric approach

- CUPED and Variance Reduction - Pre-experiment adjustment

Key Takeaway

Revenue metrics are challenging because they combine zeros, right-skew, and heavy tails. A single whale customer can dominate your experiment. Standard t-tests are technically valid but have poor power and unstable estimates. Use a combination of approaches: variance reduction (CUPED), outlier handling (Winsorization), and sensitivity analysis. Always report what you did and why—transparency about methodology is essential when analyzing heavy-tailed metrics.

References

- https://www.kdd.org/kdd2016/papers/files/Paper_573.pdf

- https://arxiv.org/abs/1803.06336

- https://engineering.linkedin.com/blog/2019/variance-reduction

- Deng, A., & Shi, X. (2016). Data-driven metric development for online controlled experiments: Seven lessons learned. *KDD*, 77-86.

- Wager, S., & Athey, S. (2018). Estimation and inference of heterogeneous treatment effects using random forests. *JASA*, 113(523), 1228-1242.

- Poyarkov, A., et al. (2016). Boosted decision tree regression adjustment for variance reduction in online controlled experiments. *KDD*, 235-244.

Frequently Asked Questions

Why can't I just use a t-test on revenue?

Should I exclude whales from my analysis?

How do I know if my data is log-normal?

Key Takeaway

Revenue metrics combine three challenges: zeros (non-purchasers), right-skew (most purchases are small), and heavy tails (occasional very large purchases). This makes means unstable, standard errors huge, and power low. Address with transformation, capping, robust methods, or specialized models—but always understand how your choice affects interpretation.