Contents

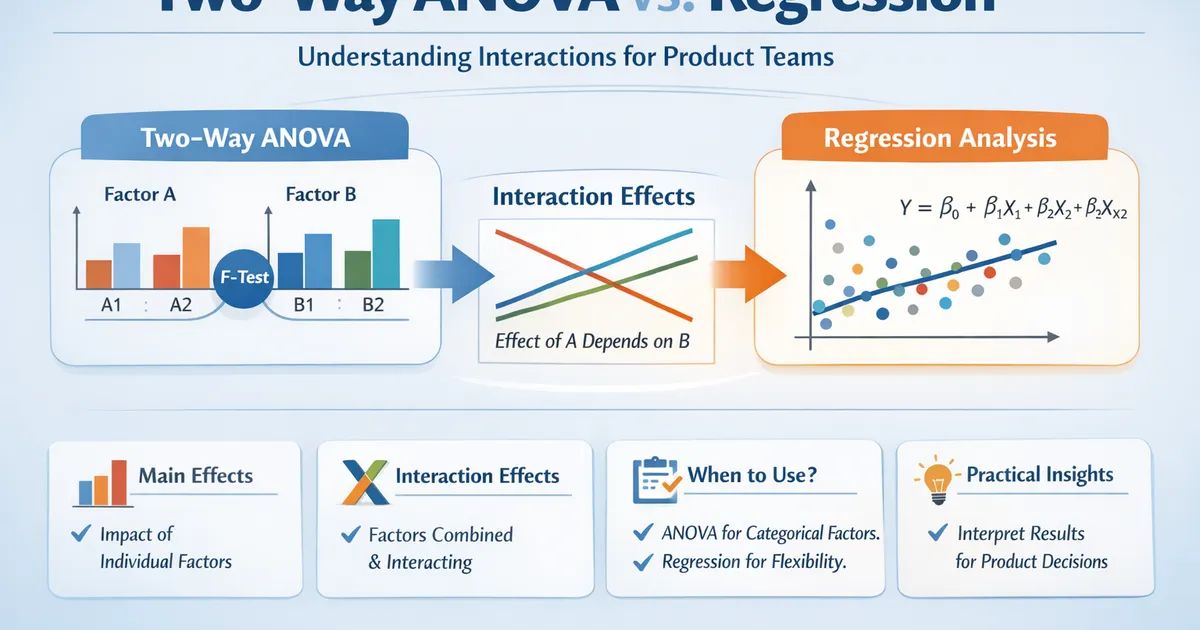

Two-Way ANOVA vs. Regression: Understanding Interactions for Product Teams

When to use two-way ANOVA versus regression for analyzing experiments with multiple factors. Covers interactions, main effects, and practical interpretation for product analytics.

Quick Hits

- •Two-way ANOVA and regression with dummy variables give identical results

- •Interactions mean the effect of one factor depends on the level of another

- •Test interactions first—if significant, main effects alone are misleading

- •Regression is more flexible; ANOVA is often easier to interpret and communicate

TL;DR

Two-way ANOVA analyzes experiments with two categorical factors, decomposing variance into main effects and interactions. It's mathematically identical to regression with dummy variables. The critical concept is interaction: when the effect of Factor A depends on the level of Factor B. Always test interactions first—if present, main effects alone are misleading.

The Setup: Factorial Designs

You're testing two factors simultaneously:

- Factor A: New feature (present/absent)

- Factor B: Device type (mobile/desktop)

Instead of running separate experiments, a factorial design tests all combinations:

| Desktop | Mobile | |

|---|---|---|

| Control | Cell 1 | Cell 2 |

| Treatment | Cell 3 | Cell 4 |

This design lets you estimate:

- Main effect of A: Overall treatment effect (averaging across devices)

- Main effect of B: Overall device effect (averaging across treatment)

- A × B Interaction: Does treatment effect differ by device?

Main Effects vs. Interactions

Main Effects

The average effect of a factor, ignoring (averaging over) the other factor.

import numpy as np

import pandas as pd

from scipy import stats

# Example data: 2x2 factorial

np.random.seed(42)

data = {

'control_desktop': np.random.normal(50, 10, 50),

'control_mobile': np.random.normal(48, 10, 50),

'treatment_desktop': np.random.normal(52, 10, 50),

'treatment_mobile': np.random.normal(58, 10, 50) # Big mobile lift!

}

# Calculate cell means

means = {k: np.mean(v) for k, v in data.items()}

print("Cell means:")

for k, v in means.items():

print(f" {k}: {v:.1f}")

# Main effect of treatment (averaging across device)

treatment_effect = ((means['treatment_desktop'] + means['treatment_mobile']) / 2 -

(means['control_desktop'] + means['control_mobile']) / 2)

print(f"\nMain effect of treatment: {treatment_effect:.1f}")

# Main effect of device (averaging across treatment)

device_effect = ((means['control_mobile'] + means['treatment_mobile']) / 2 -

(means['control_desktop'] + means['treatment_desktop']) / 2)

print(f"Main effect of device (mobile - desktop): {device_effect:.1f}")

Interactions

The effect of one factor depends on the level of another.

# Interaction: Does treatment effect differ by device?

treatment_effect_desktop = means['treatment_desktop'] - means['control_desktop']

treatment_effect_mobile = means['treatment_mobile'] - means['control_mobile']

print(f"\nTreatment effect on desktop: {treatment_effect_desktop:.1f}")

print(f"Treatment effect on mobile: {treatment_effect_mobile:.1f}")

print(f"Interaction (difference): {treatment_effect_mobile - treatment_effect_desktop:.1f}")

In this example, treatment helps mobile users much more than desktop users—that's an interaction.

Two-Way ANOVA

Python Implementation

import statsmodels.api as sm

from statsmodels.formula.api import ols

def two_way_anova(df, outcome, factor_a, factor_b):

"""

Two-way ANOVA with interaction.

"""

formula = f'{outcome} ~ C({factor_a}) * C({factor_b})'

model = ols(formula, data=df).fit()

anova_table = sm.stats.anova_lm(model, typ=2)

return model, anova_table

# Prepare data

df = pd.DataFrame({

'outcome': np.concatenate([data['control_desktop'], data['control_mobile'],

data['treatment_desktop'], data['treatment_mobile']]),

'treatment': np.repeat(['control', 'control', 'treatment', 'treatment'], 50),

'device': np.repeat(['desktop', 'mobile', 'desktop', 'mobile'], 50)

})

model, anova_table = two_way_anova(df, 'outcome', 'treatment', 'device')

print("Two-Way ANOVA Table:")

print(anova_table)

R Implementation

# Two-way ANOVA

model <- aov(outcome ~ treatment * device, data = df)

summary(model)

# Type III sums of squares (preferred for unbalanced designs)

library(car)

Anova(model, type = 3)

Interpreting the Output

The ANOVA table shows:

- treatment: Main effect of treatment

- device: Main effect of device

- treatment:device: Interaction effect

Critical rule: If interaction is significant, interpret main effects cautiously. A significant main effect of treatment may be driven entirely by one device type.

Regression Equivalent

Two-way ANOVA is identical to regression with dummy variables.

def regression_approach(df, outcome, factor_a, factor_b):

"""

Regression equivalent to two-way ANOVA.

"""

# Create dummy variables

df = df.copy()

df['treatment_dummy'] = (df[factor_a] == 'treatment').astype(int)

df['device_dummy'] = (df[factor_b] == 'mobile').astype(int)

df['interaction'] = df['treatment_dummy'] * df['device_dummy']

X = sm.add_constant(df[['treatment_dummy', 'device_dummy', 'interaction']])

y = df[outcome]

model = sm.OLS(y, X).fit()

return model

reg_model = regression_approach(df, 'outcome', 'treatment', 'device')

print("\nRegression Coefficients:")

print(reg_model.summary().tables[1])

Interpreting Coefficients

- const: Mean of reference group (control, desktop)

- treatment_dummy: Treatment effect when device = desktop (simple effect)

- device_dummy: Mobile effect when treatment = control (simple effect)

- interaction: Additional treatment effect on mobile (how much more treatment helps mobile vs. desktop)

When Interactions Matter

Crossover Interaction

Treatment helps one group but hurts another:

# Crossover interaction example

crossover_data = {

'control_desktop': np.random.normal(50, 10, 50),

'control_mobile': np.random.normal(50, 10, 50),

'treatment_desktop': np.random.normal(55, 10, 50), # Helps desktop

'treatment_mobile': np.random.normal(45, 10, 50) # Hurts mobile!

}

# Main effect might show no difference (effects cancel out)

# But interaction reveals the real story

Ordinal Interaction

Treatment helps both groups, but more for one:

# Ordinal interaction (our original example)

# Treatment helps both, but mobile benefits more

# Main effect still meaningful but incomplete

Visualization

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

def interaction_plot(df, outcome, factor_a, factor_b):

"""

Create interaction plot showing cell means.

"""

means = df.groupby([factor_a, factor_b])[outcome].mean().unstack()

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(8, 6))

for col in means.columns:

ax.plot(means.index, means[col], marker='o', linewidth=2, label=col)

ax.set_xlabel(factor_a)

ax.set_ylabel(f'Mean {outcome}')

ax.set_title('Interaction Plot')

ax.legend(title=factor_b)

# Parallel lines = no interaction

# Non-parallel lines = interaction

plt.tight_layout()

return fig

interaction_plot(df, 'outcome', 'treatment', 'device')

plt.show()

Interpreting interaction plots:

- Parallel lines → No interaction

- Non-parallel lines → Interaction present

- Crossing lines → Crossover interaction

When to Use Which

| Situation | Recommended |

|---|---|

| Two categorical factors | Either (equivalent) |

| Categorical + continuous | Regression (ANCOVA) |

| Multiple continuous | Regression |

| Need simple effect tests | Regression |

| Communication to non-stats audience | ANOVA (terms are clearer) |

| Unbalanced design | Regression (or Type III ANOVA) |

Common Mistakes

Ignoring Interactions

Testing only main effects misses the story. Always include interactions initially; remove only if clearly non-significant.

Interpreting Main Effects with Significant Interaction

With a crossover interaction, main effects can be zero or misleading. Report simple effects (effect at each level of the other factor) instead.

Type I vs. Type III Sums of Squares

For unbalanced designs, Type I (sequential) SS depends on order of factors. Use Type II or III for unbalanced data.

# Type III sums of squares

from statsmodels.stats.anova import anova_lm

anova_lm(model, typ=3) # Type III

Practical Product Example

Testing a new checkout flow (treatment) across device types:

def analyze_ab_test_with_segments(df, metric, treatment_col, segment_col):

"""

Analyze A/B test with segment interactions.

"""

# 1. Overall treatment effect

control = df[df[treatment_col] == 'control'][metric]

treatment = df[df[treatment_col] == 'treatment'][metric]

overall_lift = treatment.mean() - control.mean()

# 2. Two-way ANOVA for interaction

model, anova_table = two_way_anova(df, metric, treatment_col, segment_col)

# 3. Simple effects by segment

segments = df[segment_col].unique()

simple_effects = {}

for seg in segments:

seg_data = df[df[segment_col] == seg]

c = seg_data[seg_data[treatment_col] == 'control'][metric]

t = seg_data[seg_data[treatment_col] == 'treatment'][metric]

lift = t.mean() - c.mean()

_, p = stats.ttest_ind(c, t)

simple_effects[seg] = {'lift': lift, 'p_value': p}

return {

'overall_lift': overall_lift,

'anova_table': anova_table,

'interaction_p': anova_table.loc[f'C({treatment_col}):C({segment_col})', 'PR(>F)'],

'simple_effects': simple_effects

}

result = analyze_ab_test_with_segments(df, 'outcome', 'treatment', 'device')

print(f"Overall lift: {result['overall_lift']:.1f}")

print(f"Interaction p-value: {result['interaction_p']:.4f}")

print("\nSimple effects by device:")

for seg, effects in result['simple_effects'].items():

print(f" {seg}: lift = {effects['lift']:.1f}, p = {effects['p_value']:.4f}")

Related Methods

- Comparing More Than Two Groups — The pillar guide

- Interaction Terms in Regression — Regression perspective

- Controlling Covariates: ANCOVA vs. Regression — Adding continuous covariates

Key Takeaway

Two-way ANOVA and regression are mathematically equivalent for categorical factors. The key insight is interactions: when the effect of one factor depends on another, interpreting main effects alone is misleading. Always test interactions before interpreting main effects, and visualize with interaction plots.

References

- https://www.jstor.org/stable/2683903

- https://psycnet.apa.org/record/1980-25720-001

- Maxwell, S. E., & Delaney, H. D. (2004). *Designing Experiments and Analyzing Data* (2nd ed.). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Cohen, J., Cohen, P., West, S. G., & Aiken, L. S. (2003). *Applied Multiple Regression/Correlation Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences* (3rd ed.). Routledge.

- Kutner, M. H., Nachtsheim, C. J., Neter, J., & Li, W. (2005). *Applied Linear Statistical Models* (5th ed.). McGraw-Hill.

Frequently Asked Questions

When should I use two-way ANOVA vs. regression?

What does an interaction mean in practical terms?

Should I always test for interactions?

Key Takeaway

Two-way ANOVA and regression are mathematically equivalent for categorical factors. The key insight is interactions: when the effect of one factor depends on another, interpreting main effects alone is misleading. Always test interactions before interpreting main effects.