Contents

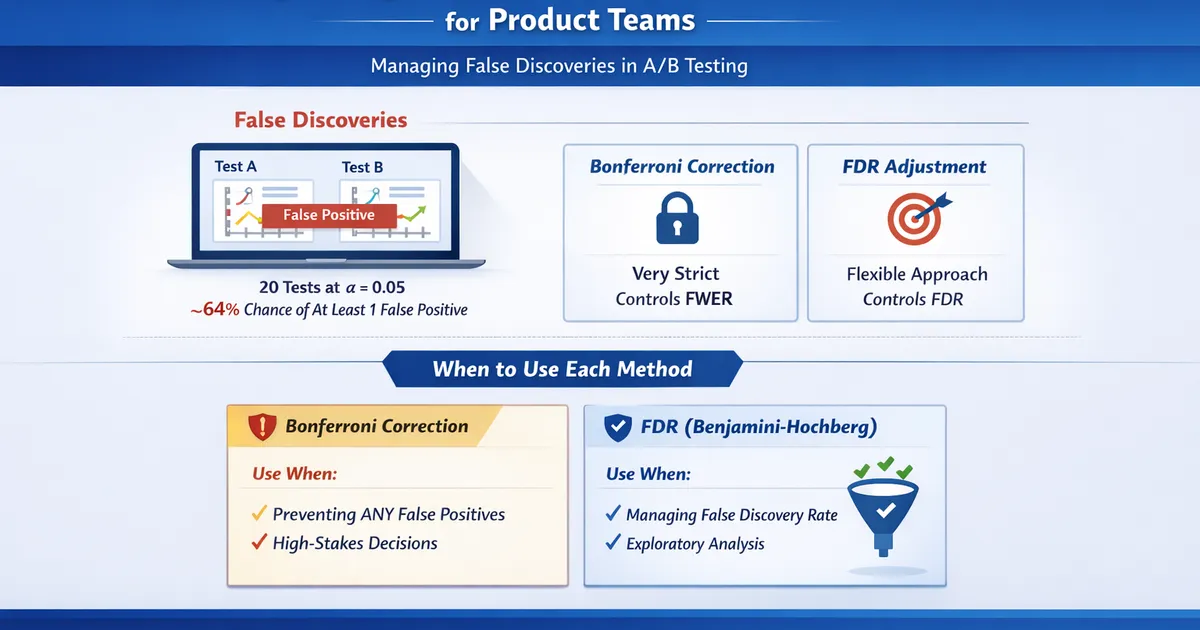

Multiple Experiments: FDR vs. Bonferroni for Product Teams

How to manage false discoveries when running many A/B tests simultaneously. Learn when to use Bonferroni, Benjamini-Hochberg FDR, and when corrections aren't needed.

Quick Hits

- •Running 20 tests at α = 0.05 with all nulls true gives ~64% chance of at least one false positive

- •Bonferroni controls FWER (any false positive) but is often too conservative

- •Benjamini-Hochberg controls FDR (proportion of false discoveries) and is usually the better choice

- •Separate experiments on different features often don't need correction—only correct within a 'family'

TL;DR

When you test many hypotheses—multiple metrics, segments, or variants—some will appear significant by chance. Bonferroni correction is conservative (divides by number of tests) but controls the probability of any false positive. Benjamini-Hochberg FDR control is less conservative and controls the expected proportion of false discoveries. For most product teams, FDR control is the right balance between power and false positive protection.

The Problem: Multiple Comparisons Inflate False Positives

At , each test has a 5% false positive rate. But what happens when you run many tests?

If you run m independent tests with all null hypotheses true:

| Number of Tests | |

|---|---|

| 1 | 5.0% |

| 5 | 22.6% |

| 10 | 40.1% |

| 20 | 64.2% |

| 50 | 92.3% |

| 100 | 99.4% |

With 20 metrics, you have nearly 2-in-3 odds of at least one spurious "win."

Two Philosophies: FWER vs. FDR

Family-Wise Error Rate (FWER)

FWER is the probability of making at least one Type I error across all tests. Bonferroni and related methods control FWER.

Question answered: "What's the chance I make ANY false discovery?"

When appropriate:

- Any false positive has serious consequences

- Small number of comparisons

- Confirmatory studies where you want strong guarantees

False Discovery Rate (FDR)

FDR is the expected proportion of rejected hypotheses that are false positives. Benjamini-Hochberg and related methods control FDR.

Question answered: "Among my discoveries, what proportion are false?"

When appropriate:

- Many comparisons (metrics, segments, variants)

- Exploratory analysis

- Can tolerate some false discoveries if most are real

Method 1: Bonferroni Correction

The simplest FWER control: divide by the number of tests.

The Method

With m tests, use significance threshold for each test.

def bonferroni_correction(p_values, alpha=0.05):

"""

Apply Bonferroni correction to a list of p-values.

Returns:

List of booleans indicating which hypotheses to reject

"""

m = len(p_values)

adjusted_alpha = alpha / m

rejections = [p < adjusted_alpha for p in p_values]

return {

'adjusted_alpha': adjusted_alpha,

'rejections': rejections,

'n_rejected': sum(rejections)

}

# Example: 10 p-values from different metrics

p_values = [0.001, 0.008, 0.015, 0.03, 0.04, 0.049, 0.06, 0.12, 0.35, 0.89]

result = bonferroni_correction(p_values)

print(f"Adjusted alpha: {result['adjusted_alpha']}")

print(f"Rejected: {result['n_rejected']} hypotheses")

# Output: Adjusted alpha: 0.005, Rejected: 2 hypotheses

R Implementation

# Built-in Bonferroni adjustment

p_values <- c(0.001, 0.008, 0.015, 0.03, 0.04, 0.049, 0.06, 0.12, 0.35, 0.89)

adjusted <- p.adjust(p_values, method = "bonferroni")

print(adjusted)

# Reject where adjusted p < 0.05

When Bonferroni Is Too Conservative

Bonferroni assumes worst-case independence and applies maximum correction. Problems:

- Power loss: With many tests, adjusted becomes tiny

- Pessimistic: If some nulls are false, you're over-correcting

- Ignores correlation: Correlated tests need less correction

With 100 metrics, Bonferroni requires for significance—you'll miss real effects.

Method 2: Benjamini-Hochberg (FDR Control)

The standard FDR control method, less conservative than Bonferroni while still protecting against false discoveries.

The Method

- Sort p-values from smallest to largest:

- Find the largest k such that

- Reject all hypotheses with p-values

import numpy as np

def benjamini_hochberg(p_values, alpha=0.05):

"""

Apply Benjamini-Hochberg FDR control.

Returns:

Dictionary with rejections and adjusted p-values

"""

m = len(p_values)

sorted_indices = np.argsort(p_values)

sorted_pvals = np.array(p_values)[sorted_indices]

# BH thresholds

thresholds = [(i + 1) / m * alpha for i in range(m)]

# Find largest k where p_(k) <= threshold

rejected = sorted_pvals <= thresholds

if np.any(rejected):

max_k = np.max(np.where(rejected)[0])

# Reject all hypotheses up to max_k

rejected = np.zeros(m, dtype=bool)

rejected[:max_k + 1] = True

else:

rejected = np.zeros(m, dtype=bool)

# Map back to original order

original_order_rejected = np.zeros(m, dtype=bool)

original_order_rejected[sorted_indices] = rejected

# Compute adjusted p-values

adjusted_pvals = np.zeros(m)

for i in range(m - 1, -1, -1):

if i == m - 1:

adjusted_pvals[sorted_indices[i]] = sorted_pvals[i]

else:

adjusted_pvals[sorted_indices[i]] = min(

adjusted_pvals[sorted_indices[i + 1]],

sorted_pvals[i] * m / (i + 1)

)

return {

'rejections': original_order_rejected.tolist(),

'adjusted_pvals': adjusted_pvals.tolist(),

'n_rejected': sum(original_order_rejected)

}

# Same example as before

p_values = [0.001, 0.008, 0.015, 0.03, 0.04, 0.049, 0.06, 0.12, 0.35, 0.89]

result = benjamini_hochberg(p_values)

print(f"Rejected: {result['n_rejected']} hypotheses")

print(f"Adjusted p-values: {[f'{p:.4f}' for p in result['adjusted_pvals']]}")

# Output: Rejected: 5 hypotheses (vs. 2 with Bonferroni!)

R Implementation

p_values <- c(0.001, 0.008, 0.015, 0.03, 0.04, 0.049, 0.06, 0.12, 0.35, 0.89)

adjusted <- p.adjust(p_values, method = "BH")

print(adjusted)

# Reject where adjusted p < 0.05

Using statsmodels

from statsmodels.stats.multitest import multipletests

p_values = [0.001, 0.008, 0.015, 0.03, 0.04, 0.049, 0.06, 0.12, 0.35, 0.89]

# Benjamini-Hochberg

reject_bh, adjusted_bh, _, _ = multipletests(p_values, alpha=0.05, method='fdr_bh')

print(f"BH rejects: {sum(reject_bh)}")

# Bonferroni for comparison

reject_bon, adjusted_bon, _, _ = multipletests(p_values, alpha=0.05, method='bonferroni')

print(f"Bonferroni rejects: {sum(reject_bon)}")

When to Apply Corrections

The key concept is the family of hypotheses—tests that should be considered together.

DO Correct Within an Experiment

Multiple metrics: Testing revenue, conversion, engagement simultaneously in one experiment. These are related hypotheses about the same treatment.

Multiple segments: Testing effect on mobile vs. desktop, US vs. EU. If you'll highlight whichever is significant, that's multiple comparisons.

Multiple variants: Testing 5 different button colors against control. Without correction, expected false positives compound.

DON'T Correct Across Independent Experiments

Different features: Testing checkout flow in one experiment, homepage layout in another. These are separate decisions on separate features.

Different time periods: This week's experiment vs. last week's. Sequential experiments are typically treated independently.

Different teams: Team A's experiments and Team B's experiments don't need joint correction unless decisions are connected.

The Practical Rule

Ask: "Are these hypotheses tested in service of the same decision?" If yes, correct. If they're separate decisions, treat separately.

Hierarchical Approach

A practical middle ground used by many product teams:

Primary Metric

Designate ONE primary metric before the experiment. This is your ship/no-ship decision and requires no correction—it's a single test.

Secondary Metrics

Monitor secondary metrics for understanding and guardrails. Apply FDR correction if you're making claims about these.

Exploratory Analysis

Segment analysis and additional metrics are exploratory. Document as hypothesis-generating, not confirmatory.

def hierarchical_analysis(primary_p, secondary_pvals, exploratory_pvals, alpha=0.05):

"""

Hierarchical approach to multiple testing.

"""

results = {}

# Primary: no correction, single test

results['primary'] = {

'p_value': primary_p,

'significant': primary_p < alpha,

'status': 'confirmatory'

}

# Secondary: FDR correction

if secondary_pvals:

reject, adjusted, _, _ = multipletests(secondary_pvals, alpha=alpha, method='fdr_bh')

results['secondary'] = {

'adjusted_pvals': adjusted.tolist(),

'significant': reject.tolist(),

'status': 'secondary (FDR-controlled)'

}

# Exploratory: flag but don't correct

results['exploratory'] = {

'pvals': exploratory_pvals,

'status': 'exploratory (no correction, hypothesis-generating only)'

}

return results

Method Comparison

| Method | Controls | Conservativeness | Best For |

|---|---|---|---|

| None | Nothing | None | Single hypothesis, separate experiments |

| Bonferroni | FWER | Very conservative | High-stakes, few comparisons |

| Holm | FWER | Less conservative than Bonferroni | High-stakes, many comparisons |

| Benjamini-Hochberg | FDR | Moderate | Most product analytics |

| Benjamini-Yekutieli | FDR (dependent) | More conservative than BH | Correlated tests |

Quick Decision Guide

Are these related hypotheses in one decision?

├── No → Don't correct

└── Yes → How bad is a false positive?

├── Very bad → Bonferroni or Holm (FWER)

└── Tolerable if few → Benjamini-Hochberg (FDR)

Common Mistakes

Correcting Everything

Applying Bonferroni across your entire experiment program tanks power and isn't necessary. Corrections apply within families of related hypotheses.

Ignoring the Problem

"We don't correct" means your reported significant results have inflated false positive rates. At minimum, document the number of comparisons made.

Post-Hoc Correction Selection

Choosing the correction method after seeing results is p-hacking. Pre-specify your correction approach.

Reporting Uncorrected P-Values

If you corrected, report adjusted p-values. Don't report "" when adjusted .

Practical Example

You run an experiment with:

- 1 primary metric (conversion rate)

- 3 secondary metrics (revenue, sessions, retention)

- 5 segment cuts (mobile/desktop × new/returning × 3 countries)

# Primary metric

primary_p = 0.023 # Significant at 0.05

# Secondary metrics

secondary_pvals = [0.041, 0.012, 0.089] # revenue, sessions, retention

# Apply FDR to secondary

from statsmodels.stats.multitest import multipletests

reject, adjusted, _, _ = multipletests(secondary_pvals, method='fdr_bh')

print("Primary metric (no correction):")

print(f" p = {primary_p:.3f} → {'SIGNIFICANT' if primary_p < 0.05 else 'not significant'}")

print("\nSecondary metrics (FDR-corrected):")

for name, p, adj, sig in zip(['Revenue', 'Sessions', 'Retention'],

secondary_pvals, adjusted, reject):

print(f" {name}: p = {p:.3f}, adjusted = {adj:.3f} → {'SIGNIFICANT' if sig else 'not significant'}")

# Segment analysis - exploratory only

print("\nSegment analysis:")

print(" [Exploratory - hypothesis generating only, no formal inference]")

Output:

Primary metric (no correction):

p = 0.023 → SIGNIFICANT

Secondary metrics (FDR-corrected):

Revenue: p = 0.041, adjusted = 0.062 → not significant

Sessions: p = 0.012, adjusted = 0.036 → SIGNIFICANT

Retention: p = 0.089, adjusted = 0.089 → not significant

Segment analysis:

[Exploratory - hypothesis generating only, no formal inference]

Related Methods

- A/B Testing Statistical Methods for Product Teams — Complete guide to A/B testing

- Sequential Testing — Another source of multiple comparisons

- Common Analyst Mistakes — Avoiding p-hacking

Frequently Asked Questions

Q: Should I correct for multiple variants (A/B/C/D testing)? A: Yes. Use Dunnett's test or apply FDR correction when comparing each variant to control.

Q: What about Holm's step-down procedure? A: Holm controls FWER like Bonferroni but is uniformly more powerful. Use it when you need FWER control but Bonferroni is too conservative.

Q: How do correlated tests affect correction? A: Positive correlation among tests means standard corrections (which assume independence) are conservative. Benjamini-Yekutieli handles arbitrary dependence but is more conservative.

Q: My organization doesn't believe in multiple testing correction. What do I do? A: At minimum, document the number of comparisons. Show simulations demonstrating false positive inflation. Advocate for at least FDR control on secondary metrics.

Key Takeaway

Use Benjamini-Hochberg FDR control when analyzing multiple metrics or segments within an experiment. Use Bonferroni only when any single false positive is unacceptable. And remember: many separate experiments on different features don't need correction—the "family" of hypotheses being tested together is what matters.

References

- https://www.jstor.org/stable/2346101

- https://www.stat.cmu.edu/~genovese/papers/fdr.pdf

- Benjamini, Y., & Hochberg, Y. (1995). Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. *Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series B*, 57(1), 289-300.

- Holm, S. (1979). A simple sequentially rejective multiple test procedure. *Scandinavian Journal of Statistics*, 6(2), 65-70.

- Hochberg, Y., & Tamhane, A. C. (1987). *Multiple Comparison Procedures*. Wiley.

Frequently Asked Questions

Do I need to correct across all experiments my company runs?

When is Bonferroni appropriate?

What's the practical difference between FWER and FDR control?

Key Takeaway

Use Benjamini-Hochberg FDR control when analyzing multiple metrics or segments within an experiment. Use Bonferroni only when any single false positive is unacceptable. And remember: many separate experiments don't need correction—the 'family' of hypotheses matters.