Contents

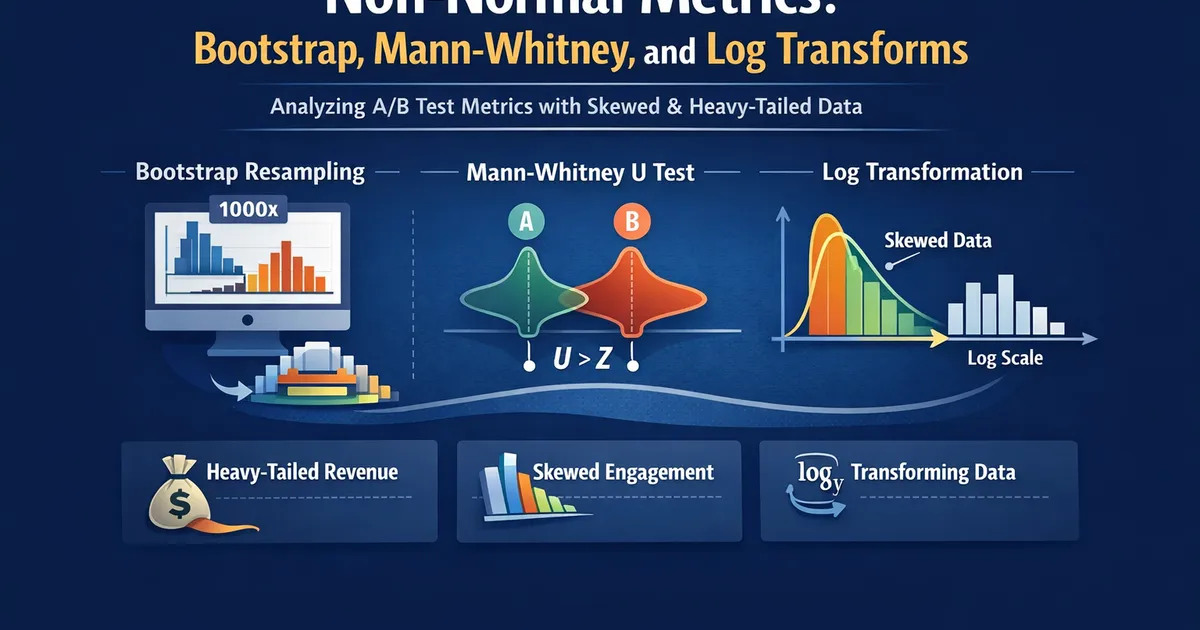

Non-Normal Metrics: Bootstrap, Mann-Whitney, and Log Transforms

How to analyze A/B test metrics that aren't normally distributed—heavy-tailed revenue, skewed engagement, and other messy real-world data. Covers bootstrap methods, Mann-Whitney U, and when transformations help.

Quick Hits

- •The t-test is surprisingly robust—with n > 30 per group, moderate skew rarely matters

- •Bootstrap methods work for any metric and provide honest uncertainty estimates

- •Mann-Whitney tests stochastic dominance, not mean difference—know what you're testing

- •Log transforms test geometric means, which may not be the business question you want to answer

TL;DR

Product metrics are messy—revenue has whales, session times have zombies, engagement has power users. These distributions violate normality assumptions. But don't panic: t-tests are robust to moderate non-normality with large samples. When they're not enough, bootstrap methods handle anything. Mann-Whitney tests a different question (dominance, not means), and log transforms change what you're measuring. Choose based on your actual question.

When Non-Normality Matters

The Central Limit Theorem Saves You (Usually)

The t-test assumes the sampling distribution of the mean is normal. Thanks to the Central Limit Theorem, this is approximately true for large samples even when individual observations are non-normal.

Rules of thumb:

- n > 30 per group: t-test is robust to moderate skew

- n > 100 per group: t-test handles substantial skew

- n > 1000 per group: t-test works for almost anything

import numpy as np

from scipy import stats

def simulate_ttest_robustness(distribution, n_per_group, n_simulations=10000):

"""

Simulate t-test under non-normal data to check Type I error.

"""

significant = 0

for _ in range(n_simulations):

# Generate from non-normal distribution (same for both groups = null true)

control = distribution(n_per_group)

treatment = distribution(n_per_group)

_, p = stats.ttest_ind(control, treatment)

if p < 0.05:

significant += 1

return significant / n_simulations

# Test with exponential distribution (very skewed)

exponential = lambda n: np.random.exponential(1, n)

for n in [10, 30, 100, 1000]:

fp_rate = simulate_ttest_robustness(exponential, n)

print(f"n={n:4d}: False positive rate = {fp_rate:.3f} (should be ~0.05)")

# Output (typical):

# n= 10: False positive rate = 0.062 (elevated)

# n= 30: False positive rate = 0.052 (close)

# n= 100: False positive rate = 0.050 (good)

# n=1000: False positive rate = 0.050 (excellent)

When You Should Worry

- Small samples: n < 30 per group with obvious non-normality

- Extreme outliers: A few values 100x larger than typical

- Heavy tails: Distributions where extreme values dominate the mean

- Bimodal/multimodal: Distinct subpopulations in your data

Method 1: Bootstrap

Bootstrap resampling is the universal solution for non-normal data. It makes no distributional assumptions and works for any statistic.

The Idea

- Resample your data with replacement, creating many "bootstrap samples"

- Compute your statistic on each bootstrap sample

- Use the distribution of bootstrap statistics for inference

Python Implementation

import numpy as np

from scipy import stats

def bootstrap_mean_diff(control, treatment, n_bootstrap=10000, alpha=0.05):

"""

Bootstrap confidence interval for difference in means.

"""

diffs = []

for _ in range(n_bootstrap):

c_sample = np.random.choice(control, size=len(control), replace=True)

t_sample = np.random.choice(treatment, size=len(treatment), replace=True)

diffs.append(np.mean(t_sample) - np.mean(c_sample))

diffs = np.array(diffs)

# Percentile confidence interval

ci_lower = np.percentile(diffs, 100 * alpha / 2)

ci_upper = np.percentile(diffs, 100 * (1 - alpha / 2))

# P-value (two-sided test of no difference)

observed_diff = np.mean(treatment) - np.mean(control)

# Null distribution: shift treatment to have same mean as control

treatment_null = treatment - np.mean(treatment) + np.mean(control)

null_diffs = []

for _ in range(n_bootstrap):

c_sample = np.random.choice(control, size=len(control), replace=True)

t_sample = np.random.choice(treatment_null, size=len(treatment_null), replace=True)

null_diffs.append(np.mean(t_sample) - np.mean(c_sample))

null_diffs = np.array(null_diffs)

p_value = np.mean(np.abs(null_diffs) >= np.abs(observed_diff))

return {

'difference': observed_diff,

'ci_lower': ci_lower,

'ci_upper': ci_upper,

'p_value': p_value

}

# Example with heavy-tailed revenue data

np.random.seed(42)

# Simulate revenue: most users spend $0-50, some spend $500+

control = np.concatenate([

np.random.exponential(10, 900), # Regular users

np.random.exponential(200, 100) # Whales

])

treatment = np.concatenate([

np.random.exponential(11, 900), # 10% lift for regular users

np.random.exponential(200, 100) # Same whales

])

result = bootstrap_mean_diff(control, treatment)

print(f"Difference: ${result['difference']:.2f}")

print(f"95% CI: [${result['ci_lower']:.2f}, ${result['ci_upper']:.2f}]")

print(f"P-value: {result['p_value']:.4f}")

R Implementation

library(boot)

# Bootstrap function for mean difference

mean_diff <- function(data, indices) {

d <- data[indices, ]

return(mean(d[d$group == "treatment", "value"]) -

mean(d[d$group == "control", "value"]))

}

# Create data frame

df <- data.frame(

value = c(control, treatment),

group = rep(c("control", "treatment"), c(length(control), length(treatment)))

)

# Run bootstrap

boot_result <- boot(df, mean_diff, R = 10000)

boot.ci(boot_result, type = "perc")

When Bootstrap Shines

- Complex metrics: Ratios, percentiles, medians

- Heavily skewed data: Revenue, session duration

- Small samples: When CLT may not apply

- Non-standard statistics: Any function of your data

Bootstrap Limitations

- Computationally expensive: 10,000+ resamples needed

- Assumes representative sample: Garbage in, garbage out

- Doesn't fix selection bias: Bootstrap estimates uncertainty, not bias

- Heavy tails need more resamples: Rare outliers need more samples to capture

Method 2: Mann-Whitney U Test

Mann-Whitney (also called Wilcoxon rank-sum) is a non-parametric test that doesn't assume normality. But beware: it tests something different than the t-test.

What Mann-Whitney Tests

Mann-Whitney tests stochastic dominance: the probability that a randomly selected treatment observation exceeds a randomly selected control observation.

This is NOT the same as "means differ." Two groups can have:

- Same mean but different Mann-Whitney result (different shape)

- Different mean but same Mann-Whitney result (symmetric shifts)

Python Implementation

from scipy import stats

def mann_whitney_test(control, treatment):

"""

Mann-Whitney U test for stochastic dominance.

"""

stat, p_value = stats.mannwhitneyu(control, treatment, alternative='two-sided')

# Probability that treatment > control

n1, n2 = len(control), len(treatment)

prob_treatment_greater = stat / (n1 * n2)

return {

'u_statistic': stat,

'p_value': p_value,

'prob_treatment_greater': prob_treatment_greater

}

result = mann_whitney_test(control, treatment)

print(f"P-value: {result['p_value']:.4f}")

print(f"P(treatment > control): {result['prob_treatment_greater']:.3f}")

R Implementation

wilcox.test(treatment, control)

When to Use Mann-Whitney

- Testing whether treatment "tends to be higher" (not means)

- Ordinal data (rankings, Likert scales)

- When the business question is about typical values, not totals

- As a robustness check alongside t-test

When NOT to Use Mann-Whitney

- When you specifically care about means (use bootstrap instead)

- When you'll report effect size as mean difference

- When business impact is calculated from totals (revenue per user × users = total revenue)

Method 3: Log Transform

Log-transforming skewed data can make it more normal, enabling standard parametric tests.

What Log Transform Tests

After log transform, the t-test compares log-means. Back-transformed, this is the ratio of geometric means:

import numpy as np

# Example

values = [1, 2, 4, 8, 16]

arithmetic_mean = np.mean(values) # 6.2

geometric_mean = np.exp(np.mean(np.log(values))) # 4.0

print(f"Arithmetic mean: {arithmetic_mean}")

print(f"Geometric mean: {geometric_mean}")

The geometric mean is always the arithmetic mean, with equality only when all values are identical.

When Log Transform Is Appropriate

Multiplicative effects: If treatment causes a percentage change (10% lift for everyone), log-scale makes sense.

# Multiplicative effect example

control = np.random.exponential(100, 1000)

treatment = control * 1.1 # 10% lift for everyone

# Raw t-test

_, p_raw = stats.ttest_ind(control, treatment)

# Log t-test

_, p_log = stats.ttest_ind(np.log(control), np.log(treatment))

print(f"Raw p-value: {p_raw:.4f}")

print(f"Log p-value: {p_log:.4f}")

# Log test will be more powerful here

Ratio metrics: Click-through rates, conversion rates often benefit from logit transform (log-odds).

When Log Transform Is Problematic

Zeros: log(0) = -∞. Common workaround is log(x + 1), but this changes the interpretation.

# Handling zeros

values_with_zeros = [0, 0, 0, 1, 2, 5, 10, 100]

# Option 1: log(x + 1)

log_transformed = np.log(np.array(values_with_zeros) + 1)

# Option 2: Exclude zeros and analyze separately

non_zero = [v for v in values_with_zeros if v > 0]

log_non_zero = np.log(non_zero)

# Option 3: Two-part model (see related article)

Additive effects: If treatment adds a fixed amount (everyone gets $5 off), log-scale obscures this.

Business interpretation: If stakeholders need arithmetic mean (total revenue / users), log-transformed results are confusing.

Decision Framework

Is your sample large (n > 100 per group)?

├── Yes → Is the question about means?

│ ├── Yes → T-test is probably fine (robust to non-normality)

│ └── No → Use method matching your question

└── No → Are there extreme outliers or heavy tails?

├── Yes → Bootstrap or consider trimmed means

└── No → T-test might still work; consider bootstrap for confirmation

What are you trying to test?

├── Mean difference → T-test or bootstrap

├── Median difference → Bootstrap or quantile regression

├── "Tends to be higher" → Mann-Whitney

├── Multiplicative effect → Log transform + t-test

└── Complex metric → Bootstrap

Practical Recommendation

For most A/B tests:

- Default: Welch's t-test (handles unequal variances, robust to moderate non-normality)

- Validate: Check histogram of your metric. Extreme skew? Run bootstrap as confirmation

- Report: If t-test and bootstrap agree, report t-test (simpler). If they disagree, investigate why and report bootstrap

Handling Outliers

Outliers disproportionately affect means. Options:

Winsorization

Cap extreme values at a percentile:

from scipy.stats import mstats

def winsorize(data, limits=(0.01, 0.01)):

"""Winsorize at 1st and 99th percentile by default."""

return mstats.winsorize(data, limits=limits)

# Cap at 1st and 99th percentile

control_wins = winsorize(control)

treatment_wins = winsorize(treatment)

Trimmed Means

Exclude extreme values from mean calculation:

from scipy.stats import trim_mean

# 10% trimmed mean (exclude top and bottom 5%)

control_trimmed = trim_mean(control, 0.05)

treatment_trimmed = trim_mean(treatment, 0.05)

# Yuen's test for trimmed mean difference

from scipy.stats import mstats

stat, p = mstats.ttest_ind(control, treatment, trim=0.1)

When to Use

- Pre-registered rule: Decide before seeing data

- Document clearly: Report both raw and trimmed results

- Understand impact: Trimming can change your answer substantially

Related Methods

- A/B Testing Statistical Methods for Product Teams — Complete guide to A/B testing

- Why Revenue Is Hard: Log-Normal and Heavy Tails — Deep dive into revenue distributions

- Bootstrap for Heavy-Tailed Metrics — Advanced bootstrap techniques

Frequently Asked Questions

Q: Should I test for normality before choosing a method? A: Formal normality tests are nearly useless. With large samples, they reject normality for tiny deviations that don't affect inference. With small samples, they lack power to detect meaningful non-normality. Instead, look at histograms and use domain knowledge.

Q: Is median better than mean for skewed data? A: Median is more robust to outliers but answers a different question. If business impact is calculated from totals (mean users), you need mean. Median tells you about the typical user.

Q: Can I use both t-test and Mann-Whitney? A: Yes, as a robustness check. If they give different conclusions, investigate why (likely different questions being answered or extreme outliers affecting the mean).

Q: How many bootstrap resamples do I need? A: 10,000 is standard for confidence intervals, 1,000 might suffice for point estimates. For p-values, use at least 10,000.

Key Takeaway

For most A/B tests with reasonable sample sizes, the t-test works fine despite non-normality. When it doesn't—small samples, extreme skew, or outliers—bootstrap is your Swiss Army knife. It handles any metric and gives honest confidence intervals. Use Mann-Whitney only when testing "tends to be higher" (stochastic dominance) rather than mean difference. And remember: log transforms change what you're testing.

References

- https://www.jstor.org/stable/2684360

- https://www.stat.berkeley.edu/~census/bootstrap.pdf

- Efron, B., & Tibshirani, R. J. (1993). *An Introduction to the Bootstrap*. Chapman & Hall/CRC.

- Lumley, T., Diehr, P., Emerson, S., & Chen, L. (2002). The importance of the normality assumption in large public health data sets. *Annual Review of Public Health*, 23(1), 151-169.

- Mann, H. B., & Whitney, D. R. (1947). On a test of whether one of two random variables is stochastically larger than the other. *The Annals of Mathematical Statistics*, 18(1), 50-60.

Frequently Asked Questions

When does non-normality actually matter?

Should I always log-transform revenue?

Is bootstrap always better than parametric tests?

Key Takeaway

For most A/B tests with reasonable sample sizes, the t-test works fine despite non-normality. When it doesn't, bootstrap is your Swiss Army knife—it handles any metric and gives honest confidence intervals. Use Mann-Whitney when you want to test 'tends to be higher' rather than 'mean is higher.'